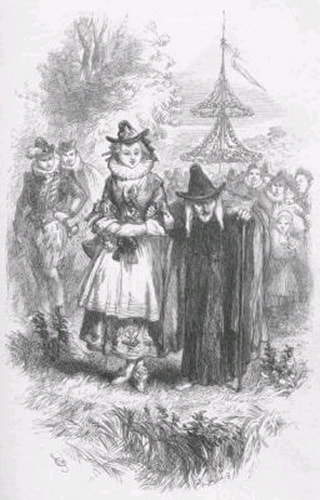

Two of the accused witches: Anne Whittle (Chattox) and her daughter Anne Redferne. Illustration by John Gilbert from the 1854 edition of William Harrison Ainsworth's The Lancashire Witches. The depiction of Chattox in traditional witches garb and her daughter in fashionable clothing is almost certainly inaccurate.

Two of the accused witches: Anne Whittle (Chattox) and her daughter Anne Redferne. Illustration by John Gilbert from the 1854 edition of William Harrison Ainsworth's The Lancashire Witches. The depiction of Chattox in traditional witches garb and her daughter in fashionable clothing is almost certainly inaccurate. The term "trial" is often applied to proceedings against alleged witches, and Miller's play presents the Salem proceedings in a trial format familiar to modern society -- but as noted, this was a convention meant to convey his underlying theme of the political atmosphere of the 1950s. The more accurate term preferred by historians and sociologists is "witch hunt" and the related term "with purge."

Although virtually all cultures in recorded history have experienced witch hunts, the term is most commonly applied to the classical period of witch-hunts in Early Modern Europe and Colonial America that took place in the Early Modern period or about 1450 to 1750, spanning the upheavals of the Reformation and the Thirty Years' War, resulting in an estimated 35,000 to 100,000 executions. Number are difficult to be registered with any certainty because many witch hunts were subsequently recognized as grave miscarriages of justice and were quietly excised from local records while others were undertaken with any governing authority to record the occurrence in the first instance.

While some sociologists have expressed the view that Early Modern witch hunts have a common origin with lynch mobs, race riots, religious intolerance movements such as the Inquisition and other forms of mob violence, the general view is that they have a distinct difference from most other forms of vigilante actions. Specifically what distinguishes a witch hunt from these other forms of societal violence is that the victims are members of the community that is meting out the punishment. Vigilantism, whether racial or religious, is usually directed at "the other," where as witch hunts are directed at "the enemy within."

Thus, while pogroms against Jewish communities were often portrayed as justified by the supposed black arts practiced by members of that faith, these were not true "witch hunts." Similarly, allegations that slaves practiced "voodoo" or other forms of evil magic were more often convenient excuses for racial violence. On factor that is common in witch hunts is there tendency to focus on social class as a factor, though there is no consistency in whether the suspect class is the wealthy, the educated, or the indigent. Accordingly, in one instance a town might rise up against the wealthy merchants, arguing that their success was not in keeping with Christian virtues of charity and modesty, while in another the people might be stirred up against the poor and criminal classes, whose degraded condition was presumed to be for want of sufficient piety. The educated were often the targets of witch hunts because their philosophical views and scientific pursuits were often viewed as unnatural or contrary to Christian values.

The witch trials in Early Modern Europe came in waves and then subsided. There were trials in the 15th and early 16th centuries, but then the witch scare went into decline, before becoming a major issue again and peaking in the 17th century; particularly during the Thirty Years War, which was essentially religious in nature, albeit one in which religion was a proxy for political interest. What had previously been a belief that some people possessed supernatural abilities (which were sometimes used to protect the people), now became a sign of a pact between the people with supernatural abilities and the devil. To justify the killings, Protestant Christianity and its proxy secular institutions deemed witchcraft as being associated to wild Satanic ritual parties in which there was naked dancing and cannibalistic infanticide (an accusation often leveled at Jews during the Middle Ages and Renaissance). It was also seen as heresy for going against the first of the ten commandments ("You shall have no other gods before me") or as violating majesty, in this case referring to the divine majesty, not the worldly. Further scripture was also frequently cited, especially the Exodus decree that "thou shalt not suffer a witch to live" (Exodus 22:18), which many supported.

The trials of the Pendle witches in 1612 are among the most famous witch trials in English history, and some of the best recorded of the 17th century. The twelve accused lived in the area surrounding Pendle Hill in Lancashire, and were charged with the murders of ten people by the use of witchcraft. The accused witches were members of two families who were in effect competitors in the begging game - that is, they essentially earned their living by presenting themselves as crippled or otherwise unsuitable for work and seeking alms -- and also in selling charms, healing potions, and likely also fortunetelling. They were also not above petty thievery and extortion by threatening to use witchcraft to harm the victim if not paid for protection. While these activities are often associated with "travelling folk" and other itinerate peoples, the two families in this instance were headed by widows who had apparently turned to these disreputable practices out of necessity. By the time of the witch hunt, each matriarch was in her 80s, one going by the "witch name" of Demdike and the other by Chattox, though whether these were names they had chosen or which were bestowed by others is not certain. Both had been regarded as witches for as much as fifty years and had been tolerated, perhaps even celebrated, for their alleged powers.

The incident that began the witch hunt occurred on March 21, 1612, when Demdike's granddaughter, Alizon Device, encountered John Law, a pedlar from Halifax, and asked him for some pins. Seventeenth-century metal pins were handmade and relatively expensive, but they were frequently needed for magical purposes, such as in healing – particularly for treating warts – divination, and for love magic, which may have been why Alizon was so keen to get hold of them and why Law was so reluctant to sell them to her. Whether she meant to buy them, as she claimed, and Law refused to undo his pack for such a small transaction, or whether she had no money and was begging for them, as Law's son Abraham claimed, is unclear. A few minutes after their encounter Alizon saw Law stumble and fall, perhaps because he suffered a stroke; he managed to regain his feet and reach a nearby inn.[18] Initially Law made no accusations against Alizon, but she appears to have been convinced of her own powers; when Abraham Law took her to visit his father a few days after the incident, she reportedly confessed, and asked for his forgiveness.

This event attracted the attention of Roger Nowell, the local Justice of the Peace, who commenced an investigation of Demdike's family and associates. In turn, Demdike's family was quick to level accusations at Chattox and her clan - possibly for revenge or in the hope of deflecting suspicion, and likely both. The result however, was that members and associates of both families were accused of witchcraft, including the two matriarchs. Most gave confessions, likely under torture, and were bound over for "trial" at the summer assizes.

All but two were tried at Lancaster Assizes on 18–19 August 1612, along with the Samlesbury witches and others, in a series of trials that have become known as the Lancashire witch trials. One was tried at York Assizes on 27 July 1612, and another died in prison. Of the eleven who went to trial – nine women and two men – ten were found guilty and executed by hanging; one was found not guilty.

The official publication of the proceedings by the clerk to the court, Thomas Potts, in his The Wonderfull Discoverie of Witches in the Countie of Lancaster, and the number of witches hanged together – nine at Lancaster and one at York – make the trials unusual for England at that time. It has been estimated that all the English witch trials between the early 15th and early 18th centuries resulted in fewer than 500 executions; this series of trials accounts for more than two per cent of that total. By way of contrast, in Germany and other European states, witch purges - the primary distinction being that all pretense of "trial" was dispensed with and the witch hunter and his crew would simply enter a community, hear accusations and carry out summary executions - could result in 500 deaths in a single season.

In England, witch-hunting would reach its apex in 1644 to 1647 due to the efforts of Puritan Matthew Hopkins. Although operating without an official Parliament commission, Hopkins (calling himself Witchfinder General) and his accomplices charged hefty fees to towns during the English Civil War. Hopkins' witch-hunting spree was brief but significant: 300 convictions and deaths are attributed to his work. Hopkins wrote a book on his methods, describing his fortuitous beginnings as a witch-hunter, the methods used to extract confessions, and the tests he employed to test the accused: stripping them naked to find the Witches' mark, the "swimming" test, and pricking the skin. The swimming test, which included throwing a witch, who was strapped to a chair, into a vat of water to see if she floated or dunking her into a pond, lake or river strapped to a chair on a pivot arm, was actually challenged for its legal validity and found to be unreliable in 1645; contrary to popular belief, there is no evidence that accused witches were drowned as a result of these tests. The 1647 book, The Discovery of Witches, soon became an influential legal text. The book was used in the American colonies as early as May 1647, when Margaret Jones was executed for witchcraft in Massachusetts, the first of 17 people executed for witchcraft in the Colonies from 1647 to 1663.

Witch-hunts began to occur in North America while Hopkins was hunting witches in England. In 1645, forty-six years before the notorious Salem witch trials, Springfield, Massachusetts experienced America's first accusations of witchcraft when husband and wife Hugh and Mary Parsons accused each other of witchcraft. In America's first witch trial, Hugh was found innocent, while Mary was acquitted of witchcraft but she was still sentenced to be hanged as punishment for the death of her child. She died in prison.[65] About eighty people throughout England's Massachusetts Bay Colony were accused of practicing witchcraft; thirteen women and two men were executed in a witch-hunt that occurred throughout New England and lasted from 1645–1663. The Salem witch trials followed in 1692–1693.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed