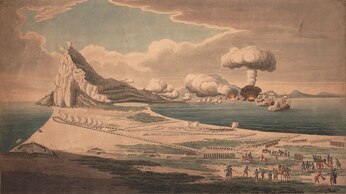

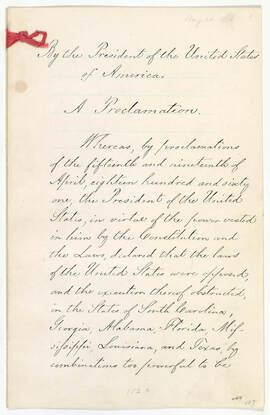

Grand Assault on Gibraltar showing the allied lines and a detonation of one of the floating batteries

Grand Assault on Gibraltar showing the allied lines and a detonation of one of the floating batteries The issue of where the American Revolution was fought is also somewhat convoluted. Certainly it was fought principally within the confines of what is now known as the United States of America, but at the time of the war, there was no clear agreement on what the United States of America was. We often forget that by 1774, the British colonial interests in North America included not just the "13 Colonies," but also "Canada" (itself divided into Upper and Lower divisions for administrative purposes, with the borders of these rather ill-defined), East and West Florida, the latter containing very little of what is today Florida and a great deal of what we think of as "New France" as well as possibly parts of Texas. And then there is "New Connecticut," the "New Hampshire Grants" and "Vermont," which, depending on who you ask, are either all the same or really quite different places. Maine of course. ar at least half of it, was part of Massachusetts, the rest being part of Canada. And let's not forget that before, during and after the revolution, Pennsylvania, New York, Connecticut, Delaware, Maryland and Virginia were contesting, both legally and occasionally military, the borders of their territories during the three Pennamite–Yankee Wars.

Then of course, there was the war at sea - or has naval historians would have it, "the Real Revolutionary War." Naval historians maintain that all the land battles of the revolution were superfluous to its outcome, which ultimately depended on naval strength. Although Britain undoubtedly had the strongest nave in the world at the time, it was also charged with administering a vast colonial empire which touched every ocean. As a result, it found it difficult to concentrate its navel forces or to devote significant forces to an one conflict for an extended period of time. While the fledgling Continental navy could not have contested against the British alone, not withstanding the superb seamanship of John Paul Jones, the French and Spanish fleets, although broadly committed to their own colonial interests, were available to balance the scales.

And it is from this Franco-Spanish commitment to aid the colonies comes the story of what might be called the only land battle of the American Revolution that took place on European soil (even this is debatable, however, depending on whether the Channel Islands are considered "European" or "British" -- so let's agree that it was the only battle of the Revolution fought on the European continent.

On June 29, 1779, French and Spanish forces invested the British colony of Gibraltar at the southern tip of Spain. By controlling Gibraltar, the British control the entrance to the Mediterranean. While Spanish forces (later reinforced by French troops) maintain a blockade of the land side, naval forces of both the Spanish and French were able to maintain only a limited blockade of the seaward approach.

Contrary to popular belief, the surrender of the British at Yorktown on October 19, 1781 did not end the American Revolution. It was not even the last battle to be fought on American soil. However, it was the battle which forced the British to sue for peace and but mid-1782 it was all but certain that a permanent peace treat was going to be approved, meaning the France and Spain would lose their "casus belli" against the British with very little to show for their effort in supporting the colonies (indeed, loses in the Caribbean, Central America and India meant the two nations were probably emerging from the war with less than they started with).

So it was that in September 1782 the French and Spanish launched an audacious plan to seize Gibraltar with a combined navel and land attack using an entirely new tactic. French engineers proposed to reduce the land batteries of the fortress by using massive floating batteries to pound the British into submission. This plan was know as the "Grand Assault" and would employ more troops and artillery than had been engaged at any point during the conflict on American soil.

For the allies it was becoming clear that the recent blockades had been a complete failure and that an attack by land would be impossible. Ideas were put forward to break the siege once and for all. The plan was proposed that a squadron of battery ships should take on the British land-based batteries and pound them into submission by numbers and weight of shots fired, before a storming party attacked from the siege works on the Isthmus and further troops were put ashore from the waiting Spanish fleet. The French engineer Jean Le Michaud d'Arçon invented and designed the floating batteries—'unsinkable' and 'unburnable'—intended to attack from the sea in tandem with other batteries bombarding the British from land.

The floating batteries would have strong, thick wooden armor—1-metre-wide timbers packed with layers of wet sand, with water pumped over them to avoid fire breaking out. In addition old cables would also deaden the fall of British shot and, as ballast, would counterbalance the guns' weight. Guns were to be fired from one side only; the starboard battery was removed completely and the port battery heavily augmented with timber and sand infill. The ten floating batteries would be supported by ships of the line and bomb ships, which would try to draw away and split up the British fire. Five batteries each with two rows of guns, together with five smaller batteries each with a single row, would provide a total of 150 guns. The Spanish enthusiastically received the proposal. D'Arçon sailed close to shore under enemy fire in a skiff to get more accurate intelligence.

On 13 September 1782 the Bourbon allies launched their great attack: 5,260 fighting men, both French and Spanish, aboard ten of the newly engineered 'floating batteries' with 138 to 212 heavy guns under the command of Don Buenaventura Moreno. Also in support were the combined Spanish and French fleet, which consisted of 49 ships of the line, 40 Spanish gunboats and 20 bomb-vessels, manned by a total of 30,000 sailors and marines under the command of Spanish Admiral Luis de Córdova. They were supported by 86 land guns and 35,000 Spanish and 7,000–8,000 French troops on land, intending to assault the fortifications once they had been demolished. An 'army' of over 80,000 spectators thronged the adjacent hills on the Spanish side, expecting to see the fortress beaten to powder and 'the British flag trailed in the dust.' Among them were the highest families in the land, including the Comte D'Artois.

The batteries slowly moved forward along the bay and one by one the 138 guns opened fire, but soon events did not go according to plan. The alignments were not correct: the two lead ships Pastora and the Tala Piedra moved further ahead than they should have. When they opened fire on their main target, the King's Battery, the British guns replied, but the cannonballs were observed to bounce off their hulls. Eventually the Spanish junks were anchored on the sandbanks near the Mole but were too spread out to create any significant damage to the British walls.

Meanwhile, after weeks of preparatory artillery fire, the 200 heavy-caliber Spanish and French guns opened up on the land side from the North directed onto the fortifications. This caused some casualties and damage, but by noon the artificers had heated up red-hot shot. Once the shot were ready, Elliot ordered them to be fired. At first the heated shot made no difference, as many were doused on board the floating batteries.

Although the batteries had anchored, a number had soon grounded and began to suffer damage to their rigging and masts. The King's Bastion blasted away at the closest ships, the Pastora and the Talla Piedra, and soon the British guns began to have an effect. Smoke was spotted coming from Talla Piedra, already severely damaged and its rigging in tatters. Panic ensued since no vessel could come and support her; nor was there any way for the ship to escape. Meanwhile, the Pastora under the Prince de Nassau began to emit a huge amount of smoke. Despite efforts to find the cause, the sailors on board were fighting a losing battle. To make matters worse, the Spanish land guns had ceased firing. It soon became apparent to de Crillon that the Spanish army had run out of powder and were already low on shot. By nightfall it was clear that the assault had failed, but worse was to come, because the fire on the two batteries was out of control. To add to de Crillon's frustration, de Córdova's ships of the line failed to move in support, and neither did Barcelo's vessels. De Crillon, acknowledging defeat and not wishing to upset the Spanish by issuing demands, soon ordered the floating batteries to be scuttled and the crews rescued. Rockets were sent up from the batteries as distress signals.

During this operation, Roger Curtis, the British naval commander, seeing the attacking force in great danger, warned Elliot about the huge potential death toll and that something must be done. Elliot agreed and had the fleet of twelve gunboats under Curtis set out with 250 men. They headed towards the Spanish gunboats, firing as they advanced, after which the Spanish precipitated a quick retreat.

Curtis's gunboats reached the batteries and one by one took them; but this soon turned into a rescue effort when they realized from prisoners that many men were still on board with the scuttling now taking place. British marines and sailors then stormed the Pastora, taking the men on board as prisoners and eventually pulled them off the doomed ship, having also seized the Spanish Royal Standard which had been flying from the stern. As this was going on, the flames that had engulfed Talla Piedra soon reached the magazine. The ensuing explosion was tremendous, with a sound that reverberated around the bay and a huge mushroom cloud of smoke and debris that rose up in the air. Many were killed on board, but the British had few casualties. The Spanish, now in panic, all reached for the British boats by jumping in the water.

Soon the Pastora, engulfed in a mass of flames, followed the fate of the Talla Piedra. The latter burnt to the water's edge and sank about 1:00 am on 14 September after having lain upwards of fourteen hours under the fire of Gibraltar. The fire reached the powder magazine and another huge explosion ensued. This time many in the water were killed outright; a British boat was sunk and the coxswain of Curtis's boat was killed when hit by debris. Nassau, Littlepage and the surviving crew managed to make their way back to shore.

Curtis realized that it was unsafe to be near the flaming batteries and soon withdrew men from two more floating batteries engulfed in flame, then finally ordered a withdrawal. The rescue operation was hindered further when Spanish batteries opened fire after receiving more powder and shot. Many more men drowned or were burned in the ensuing inferno; others were hit by their own artillery. The Spanish ceased fire only when the mistake was realized, but it was too late. The rest of the Spanish batteries blew up in similar horrific style; the explosions lofted huge mushroom clouds that rose nearly 1,000 feet in the air. Some men were still on board and those that had jumped overboard often drowned as the vast majority couldn't swim. By the early hours of the morning only two floating batteries remained. A Spanish felucca tried to set one on fire but was driven off by British guns. The two were promptly set alight by them and were finished in the same way as the others by the afternoon.

By 4:00 am, all the floating batteries had been sunk, leaving the Gibraltar waterfront a mass of debris and bodies from the wrecked Spanish ships. During the Grand Assault 40,000 rounds had been fired. Casualties in just twelve hours were heavy: 719 men on board the ships (many of whom drowned) were casualties.

Curtis had rescued a further 357 officers and men, who thus became prisoners, while in the siege lines more casualties brought up the allied total to 1,473 men for the Grand Assault, with all ten floating batteries destroyed.[106] The engagement was the fiercest battle of the American Revolutionary War. The British lost 15 killed and 68 men were wounded, nearly half of them from the Royal Artillery. A Royal Marine who had taken Pastora's large Spanish color later presented it to Elliot.

One of the survivors who had been on a floating battery that had blown up was Louis Littlepage. He was saved and managed to get back to the Spanish fleet.

For Elliot and the garrison it was a great victory and for the allies it was a brutal defeat, with their plans and hopes in tatters. De Córdova was heavily criticized for not coming to help the batteries, while d'Arçon and de Crillon threw accusations and recriminations at each other. In Spain the news was met with consternation and despair. The huge crowds that had been promised a crushing victory left the area chagrined.

On 14 September 1782, the assault by the allies by land which was supposed to have been a "mopping up" operation was initially going to be attempted. The Spanish army formed up behind the batteries at the northern end of the Isthmus. At the same time, the Spanish ships moved across the bay, packed with more troops. However, de Crillon cancelled the assault, judging that losses would have been huge. Gibraltar nevertheless remained under siege, but Spanish bombardments decreased to about 200 rounds a day as both sides knew of the impending peace treaty.

From 20 September, reports of the great French and Spanish assault on Gibraltar began to reach Paris. By 27 September it was clear that the operation, involving more troops than had ever been in service at one time on the entire North American continent, had been a horrific disaster. In Madrid news of the failure was received with dismay; the King was in mute despair as he read the intelligence reports at the Palace of San Ildefonso. The French had done all they could to help the Spanish achieve their essential war aim, and began serious discussions on alternative exit strategies, urging Spain to offer Britain some very large concessions in return for Gibraltar.

News also reached the British, ecstatic at the outcome, and at the same time just as John Jay submitted his draft treaty. The British promptly stiffened their terms, flatly refusing to cede land north of the old border with Canada. They also insisted that the Americans pay their national pre-war debt to the British or compensate Loyalists for their seized property. As a result, the Americans were forced to agree to these terms, and their Northern frontier was established along the line of the Great Lakes. Preliminary Articles of Peace were to be signed between the two on 30 November.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed