Bolesław the Pious

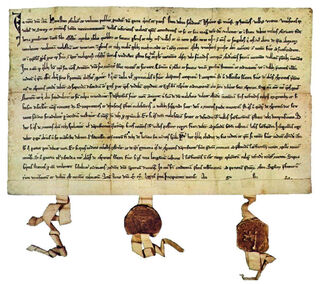

Bolesław the Pious In the 20th century, some scholars supported the view that both the original Statute of Kalisz and its authenticated copies could not be found and that the text was a 15th-century forgery done for political purposes. Nonetheless, the statute served as a basis for Jewish privileges in Poland until 1795.

The text of the statute:

In the Name of the Lord. Amen. The deeds of humankind are fleeting, unless revived through the testimonies of witnesses, or by the testimony of documents. Therefore We, Bolesław, by the grace of God the Duke of Wielkopolska [Greater Poland], hereby make it known to both those of the present and of the future, to whose notice this present writ shall come, that to our Jews living all across the lands of our Dominion, We have resolved to declare word-for-word the statutes and privileges that they have obtained from Us, as contained in the following series of articles.

1. Firstly, we hereby ordain that with respect to any case involving money, or any property whether mobile or immobile, or in a criminal case that affects the person or property of a Jew, no Christian be admitted as a witness against a Jew, unless a Jew be together with such Christian.

2. Likewise, if a Christian implicates a Jew by stating that the Jew mortgaged what he had pawned, and the Jew disavows this, whereupon the Christian is nonetheless unwilling to believe in the honesty of the Jew’s words, then the Jew shall under oath prove his intention to return the equivalent received by him and shall then go forth, absolved.

3. If a Christian has pawned something with a Jew, and then states that he pawned it for a lesser amount of money than the Jew acknowledges, the Jew shall swear an oath with respect to what was pawned to him, and what has been evidenced under oath, the Christian shall not to decline to pay out to him.

4. Likewise, if a Jew tells a Christian, without calling on witnesses, that he [=the Christian] has borrowed [from the former] on the basis of something pawned, and he [=the Christian] denies it, the Christian may exonerate himself by his own oath alone.

5. A Jew shall be permitted to receive, by way of goods pawned, everything that may be given over to him, whatever its name be, without making investigation into the same, except for vestments stained or soaked with blood, and except sacral ones, which he shall by no means accept, whatsoever.

6. Similarly, if a Christian implicates a Jew by stating that something pawned to the Jew had been robbed from him by secret plotting or by violence, the Jew shall pledge an oath with respect to the pawned good that with the receipt of the same, he was ignorant of it having been stolen or seized; and in this oath of his he shall indicate what price was charged for the good thus pawned, and when he has thereby cleansed himself, the Christian shall reimburse to him the principal and the interest that has meanwhile accrued.

7. If, furthermore, by fire or theft or by force a Jew has lost his property together with goods he had accepted in pawn, and this has become certain, and notwithstanding this the Christian who has pawned the same implicates him, the Jew shall absolve himself by means of his own oath.

8. Similarly, if Jews have indeed excited discord amidst themselves, or a struggle, the judge of our city may claim no right for himself with respect to them, as We exclusively shall exercise judgement, or our Palatine [Voivode], or else his judge. If, however, the accusation is leveled at a person [for having harmed someone], then such a case shall be reserved exclusively for Us to be adjudged.

9. Also, if a Christian has harmed a Jew in whatever manner, the guilty party shall have to pay the fine to Us and to our Palatine. Having delivered it to our treasury, he may come upon our grace. Moreover, he shall recompense the injured party in view of healing his wounds, and of the expenses, as required and demanded by the laws of the realm.

10. Similarly, if a Christian has killed a Jew, he shall be punished with the appropriate adjudication, and all his possessions whether mobile or immobile shall be transferred to our authority.

11. Also, if a Christian has beaten a Jew in the way, nonetheless, that no blood is shed, he ought to be pursued by the Palatine, according to the custom of our land; and, having stricken or afflicted a Jew, he shall offer reparation therefor, in the manner as is customary in our land; should he indeed be not able to provide the money, then he shall be punished in fashion fitting for what he has done.

12. Wherever a Jew should transverse our Dominion, no-one shall offer any impediment to him whatsoever, nor cause or inspire any annoyance, burden, or trouble; but if he [=such a Jew] transports any merchandise or such things with him, customs shall arise therefrom at all the customs-posts, and this same Jew shall likewise pay only such duty or toll as is payable by any citizen of the city wherein the Jew abides at that time.

13. In the event that Jews, according to their custom, transport anyone of their dead either from one city to another city, or from one province to another, or from one land to another, it is our will that our customs-officers extort nothing from them. Should, however, a customs-officer extort something, it is our will that he be punished as a grave-robber.

14. Likewise, if a Christian has in any manner devastated, or invaded, a cemetery of theirs, it is our will that, in accordance with the custom and laws of our land, he be gravely punished, and all the properties of his, by whatever name these be called, be passed to our treasury.

15. If anyone imprudently throws [something/stones] at schools [i.e., synagogues] of the Jews, it is our will that he pay two talents of pepper to our Palatine.

16. Likewise, if a Jew be condemned by his Judge to a pecuniary penalty, which is called vandil, the perpetrator, if he be found guilty, shall pay to the same the penalty of a talent of pepper, as since times ancient.

17. If a Jew is summoned to court by command of his judge, and does not appear for the first nor for the second time, he must pay the judge for both of the times, in place thereof, the penalty that is customary since times ancient. If he comes neither at the third command, he shall pay to the aforementioned Judge the penalty that follows thereafter.

18. Likewise, if a Jew has wounded a Jew, he may not refuse to pay to his Judge the penalty according to the custom of our land.

19. We hereby ordain that no Jew shall swear an oath upon a Rodal Torah of theirs, unless it be for a substantial cause that extends up to fifty marcas (grzywna) of silver, or unless called to our presence; for minor matters, he indeed ought to pledge before the schools [i.e., synagogues], at the entrance-door to the said schools.

20. In the event that a Jew has secretly been killed, and the murderer’s guilt may not be proved, and if after an investigation the Jews have captured a suspect, We shall administer to the Jews the protection of justice against the suspected killer of the Jew, by means of the law regarding such a matter.

21. Also, if Christians lay a violent hand against a Jew, they shall be punished according to what the law of our land requires.

22. Likewise, the judge of the Jews shall bring no case that has emerged amongst Jews to court, unless he be invited because of a complaint. Also the Jews ought to be judged near their schools or wherever they may elect.

23. Similarly, if a Christian has redeemed from a Jew what he pawned, but has not paid the interest, the interest shall become compounded if not provided within a month.

24. Likewise, we hereby ordain that no-one seek quarters in a Jewish house.

25. If a Jew has lent money upon pawned possessions or a [hypothecation] letter for goods immobile, and he to whom the things belong offers proof of whose things those are, We ordain that the Jew be deprived of the money and the pledge of the letter.

26. Likewise, if anybody, a male or a female, has abducted a Jewish boy, we order that he be prosecuted as a thief.

27. Also, if a Jew has received pawned goods from a Christian and held the same in his possession for a year, and if the value of the goods is not in excess of the money that has been lent, the Jew shall show the goods to his Judge; and if the pawned goods are insignificant, he shall show the same to our Palatine or his own Judge, or shall have the liberty to vend it, if the same demonstrates the pawned goods to his Judge prior to the passing of a year. If indeed such goods have remained with a Jew for a year and a day, he shall thenceforth be responsible therefor before no-one.

28. It is our will that no-one dare to coerce a Jew with respect to recouping pawned goods during his celebration of a holiday, whatsoever.

29. Similarly, if any Christian would forcefully remove his pawned good(s) from a Jew, or would exercise violence in the Jew’s house, he shall be gravely punished as a plunderer of our treasury.

30. Likewise, a Jew shall not be proceeded against in judgment, except in the schools or where all the Jews are adjudicated; saving Us and our Palatine, who may summon them to our presence.

31. According to the ordinances of the Pope, in the name of our Holy Father, we strictly prohibit that, henceforth, no Jew in our Dominion should be accused that they would make use of human blood, because according to the precept of their law, Jews in their entirety absolutely refrain from blood. Yet, if any Jew be blamed for having killed a Christian boy, he ought to be convicted by three Christians and as many Jews, and afterwards proved guilty. Accordingly, this same Jew ought to be punished with the penalty appropriate for the crime committed. If however the aforesaid witnesses and his innocence exculpate him, the Christian [accuser] shall suffer because of his calumny the penalty which the Jew would have had to suffer.

32. We furthermore ordain that whatever a Jew has lent, be it gold or denarii, or silver, the same thing ought to be repaid or returned to him, together with the required interest that has accrued.

33. It is our will that Jews receive in pawn whatever horses, in general, openly and in the light of the day. If however any stolen horse has been discovered by a Christian at a Jew’s, the Jew shall exonerate himself by means of his own oath, stating that he took that same horse openly and in the day so that he could have it as a pledge pawned for a certain amount of money and did not suspect it to be stolen.

34. Similarly, we forbid lest minters established in our Dominion dare detain or seize, in whatever way, Jews with false denarii or other things, except exclusively upon our writ or that of our Palatine, or else that of respectable citizens.

35. We hereby ordain that if any Jew compelled by a dire necessity shouts aloud in the time of night and if the neighbouring Christians undertake not to offer him succour, and arrive not at the clamour, every of his neighbouring Christians shall be obligated to pay thirty soldos.

36. We moreover order that Jews may liberally vend and purchase everything, and touch bread, similarly as Christians do. Those who would prohibit them to do so shall indeed be liable to pay a penalty to our Palatine.

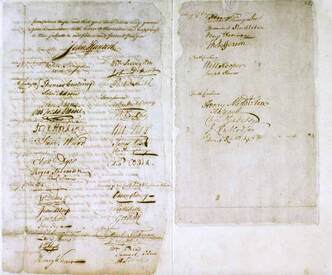

And so that all of the foregoing may obtain the strength of perpetual validity, we have given them this present instrument, with the signatures of the witnesses, for security, also fortifying it by the protection of the seal of ours; the witnesses of this matter verily are: Comes Arbeldus [resp. Archambold], Palatine of Kalisz; Comes Szymon, Castellan of Gniezno; Comes Jan of Kalisz; Comes Maciej, Castellan of Ląd; Comes Cz[ec]hosław, Butler of Kalisz; Comes Dersław, Courser of Ląd; with the other numerous Barons of our Land. Done at the city of Kalisz, on the day following the day of the Assumption of the B[lessed] V[irgin] M[ary], in the Year of our Lord one-thousand two-hundred and sixty-four, on this sixteenth day of August.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed