|

The Emergency Quota Act, also known as the Emergency Immigration Act of 1921, the Immigration Restriction Act of 1921, the Per Centum Law, and the Johnson Quota Act, was formulated mainly in response to the large influx of Southern and Eastern Europeans and successfully restricted their immigration as well as that of other "undesirables" to the United States. Although intended as temporary legislation, it proved, in the long run, the most important turning-point in American immigration policy because it added two new features to American immigration law: numerical limits on immigration and the use of a quota system for establishing those limits, which came to be known as the National Origins Formula. The use of the National Origins Formula continued until it was replaced by the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, which introduced a system of preferences, based on immigrants' skills and family relationships with US citizens or US residents.

0 Comments

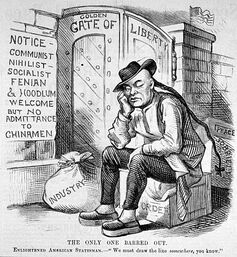

The Chinese Exclusion Act was a United States federal law signed by President Chester A. Arthur on May 6, 1882, prohibiting all immigration of Chinese laborers. Building on the earlier Page Act of 1875 which banned Chinese women from immigrating to the United States, the Chinese Exclusion Act was the first, and remains the only law to have been implemented, to prevent all members of a specific ethnic or national group from immigrating to the United States. The act followed the Angell Treaty of 1880, a set of revisions to the U.S.–China Burlingame Treaty of 1868 that allowed the U.S. to suspend Chinese immigration. The act was initially intended to last for 10 years, but was renewed and strengthened in 1892 with the Geary Act and made permanent in 1902. These laws attempted to stop all Chinese immigration into the United States for ten years, with exceptions for diplomats, teachers, students, merchants, and travelers. The laws were widely evaded. Exclusion was repealed by the Magnuson Act on December 17, 1943, which allowed 105 Chinese to enter per year. Chinese immigration later increased with the passage of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952, which abolished direct racial barriers, and later by the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, which abolished the National Origins Formula. Image: A political cartoon from 1882, showing a Chinese man being barred entry to the "Golden Gate of Liberty". The caption reads, "We must draw the line somewhere, you know."  Isabel González was a citizen of Puerto Rico who traveled to New York in 1902. Her fiancé had traveled there before her to find work, and was planning to send for her. When no word arrived of his fate, Isabel, who was carrying his child, decided to go to New York to look for him. Her brother and an aunt and uncle were already living in New York, she had all the proper documentation, and expected no problems with entry upon arrival because Puerto Rico was a US territory. Upon arriving in Ellis Island, however, she was detained and, despite efforts by her family, denied entry on the grounds that as a pregnant and unmarried woman she was likely to become a public charge and, thus, was an "undesirable alien." González thus became the focus of a civil lawsuit which eventually reached the U.S. Supreme Court. The Court concluded that person's living within American territories were not "aliens" and could not be denied entry to the US on that ground. The Court further ruled, however, that the question of whether citizenship would be extended to the people of those territories was a matter for Congress. Thirteen years after González v. Williams, the United States Congress addressed the issue of citizenship as it related to Puerto Ricans. The Jones-Shafroth Act was passed in 1917 giving the island residents citizenship. |

CTROL BlogThis blog will be used by Center Staff to post articles addressing issues concerning the Rule of Law and how it is taught and understood in our communities, nation, and world. Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed