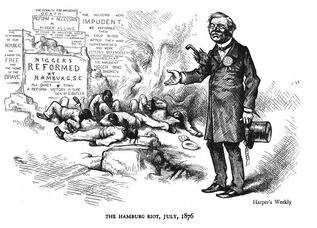

1885 riot and massacre of Chinese-American coal miners, by white miners. From Harper's Weekly: Harper's Weekly, Vol. 29

1885 riot and massacre of Chinese-American coal miners, by white miners. From Harper's Weekly: Harper's Weekly, Vol. 29 Tension between whites and Chinese immigrants in the late 19th century American West was particularly high, especially in the decade preceding the violence. The massacre in Rock Springs was one among several instances of violence culminating from years of anti-Chinese sentiment in the United States. The Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882 suspended Chinese immigration for ten years, but not before thousands of immigrants came to the American West. Most Chinese immigrants to Wyoming Territory took jobs with the railroad at first, but many ended up employed in coal mines owned by the Union Pacific Railroad. As Chinese immigration increased, so did anti-Chinese sentiment on the part of whites. The Knights of Labor, one of the foremost voices against Chinese immigrant labor, formed a chapter in Rock Springs in 1883, and most rioters were members of that organization. However, no direct connection was ever established linking the riot to the national Knights of Labor organization.

In the immediate aftermath of the riot, United States Army troops were deployed in Rock Springs. They escorted the surviving Chinese miners, most of whom had fled to Evanston, Wyoming, back to Rock Springs a week after the riot. Reaction came swiftly from the era's publications. In Rock Springs, the local newspaper endorsed the outcome of the riot, while in other Wyoming newspapers, support for the riot was limited to sympathy for the causes of the white miners. The massacre in Rock Springs touched off a wave of anti-Chinese violence, especially in the Puget Sound area of Washington Territory.

After the riot in Rock Springs, sixteen men were arrested, including Isaiah Washington, a member-elect to the territorial legislature. The men were taken to jail in Green River, where they were held until after a Sweetwater County grand jury refused to bring indictments. In explaining its decision, the grand jury declared that there was no cause for legal action, stating, in part: "We have diligently inquired into the occurrence at Rock Springs. ... [T]hough we have examined a large number of witnesses, no one has been able to testify to a single criminal act committed by any known white person that day."

Those arrested as suspects in the riot were released a little more than a month later, on October 7, 1885. On their release, they were "...met ... by several hundred men, women and children, and treated to a regular ovation", according to The New York Times. The defendants in the Rock Springs case enjoyed the same broad community consent that lynch mobs often received No person or persons were ever convicted in the violence at Rock Springs.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed