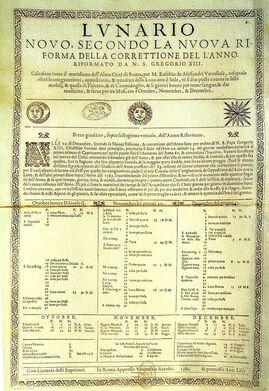

The Gregorian calendar is the calendar used in most of the world. It was introduced in October 1582 by Pope Gregory XIII as a minor modification of the Julian calendar, reducing the average year from 365.25 days to 365.2425 days, and adjusting for the drift in the 'tropical' or 'solar' year that the inaccuracy had caused during the intervening centuries. The calendar spaces leap years to make its average year 365.2425 days long, approximating the 365.2422-day tropical year that is determined by the Earth's revolution around the Sun

There were two reasons to establish the Gregorian calendar. First, the Julian calendar assumed incorrectly that the average solar year is exactly 365.25 days long, an overestimate of a little under one day per century. The Gregorian reform shortened the average (calendar) year by 0.0075 days to stop the drift of the calendar with respect to the equinoxes. Second, in the years since the First Council of Nicaea in AD 325, the excess leap days introduced by the Julian algorithm had caused the calendar to drift such that the (Northern) spring equinox was occurring well before its nominal 21 March date. This date was important to the Christian churches because it is fundamental to the calculation of the date of Easter. To reinstate the association, the reform advanced the date by 10 days: Thursday 4 October 1582 was followed by Friday 15 October 1582. In addition, the reform also altered the lunar cycle used by the Church to calculate the date for Easter, because astronomical new moons were occurring four days before the calculated dates.

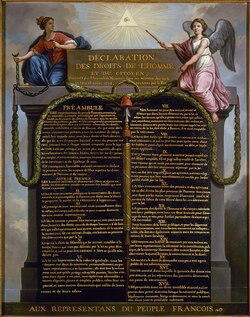

The reform was adopted initially by the Catholic countries of Europe and their overseas possessions. Over the next three centuries, the Protestant and Eastern Orthodox countries also moved to what they called the Improved calendar, with Greece being the last European country to adopt the calendar (for civil use only) in 1923.[4] To unambiguously specify a date during the transition period (in contemporary documents or in history texts), both notations were given, tagged as 'Old Style' or 'New Style' as appropriate. During the 20th century, most non-Western countries also adopted the calendar, at least for civil purposes.

Although Gregory's reform was enacted in the most solemn of forms available to the Church, the bull had no authority beyond the Catholic Church and the Papal States. The changes that he was proposing were changes to the civil calendar, over which he had no authority. They required adoption by the civil authorities in each country to have legal effect. The bull Inter gravissimas became the law of the Catholic Church in 1582, but it was not recognized by Protestant Churches, Eastern Orthodox Churches, Oriental Orthodox Churches, and a few others. Consequently, the days on which Easter and related holidays were celebrated by different Christian Churches again diverged.

Many Protestant countries initially objected to adopting a Catholic innovation; some Protestants feared the new calendar was part of a plot to return them to the Catholic fold. For example, the British could not bring themselves to adopt the Catholic system explicitly: the Annexe to their Calendar (New Style) Act 1750 established a computation for the date of Easter that achieved the same result as Gregory's rules, without actually referring to him.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed