This date is often cited as the beginning of the practice of placing indigenous peoples into reservations, but in fact that practice pre-dated the revolution. In 1764 the "Plan for the Future Management of Indian Affairs" was proposed by the British Board of Trade. Although never adopted formally, the plan established the imperial government's expectation that land would only be bought by colonial governments, not individuals, and that land would only be purchased at public meetings. Additionally, this plan dictated that the Indians would be properly consulted when ascertaining and defining the boundaries of colonial settlement. The private contracts that once characterized the sale of Indian land to various individuals and groups—from farmers to towns—were replaced by treaties between sovereigns.

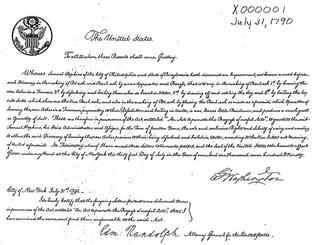

The American Indigenous Reservation system started with the Royal Proclamation of 1763, where Great Britain set aside an enormous resource for Indians in the territory of the present United States. The United States put forward another act when Congress passed the Indian Removal Act in 1830. A third act pushed through was “the federal government relocated portions of the ‘Five Civilized Tribes’ from the southeastern states in the Non-Intercourse Act of 1834.” All three of these laws set into motion the Indigenous Reservation system in the United States of America, resulting in the forceful removal of Indigenous peoples into specific land Reservations.

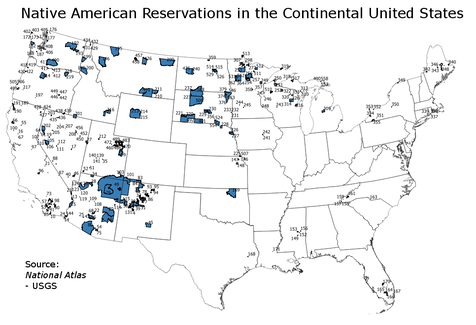

Today, there are 326 recognized reservations. The term "reservation" is a legal designation. It comes from the conception of the Native American nations as independent sovereigns at the time the U.S. Constitution was ratified. Thus, early peace treaties (often signed under conditions of duress or fraud), in which Native American nations surrendered large portions of their land to the United States, designated parcels which the nations, as sovereigns, "reserved" to themselves, and those parcels came to be called "reservations". The term remained in use after the federal government began to forcibly relocate nations to parcels of land to which they had no historical connection.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed