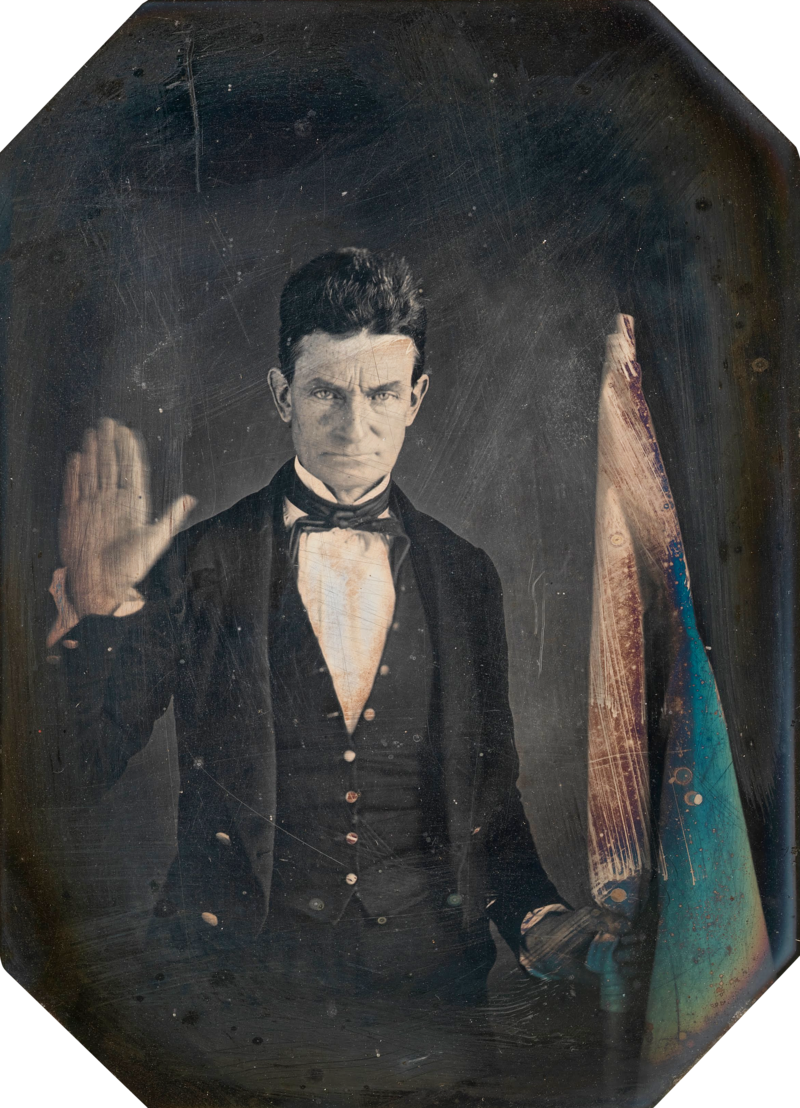

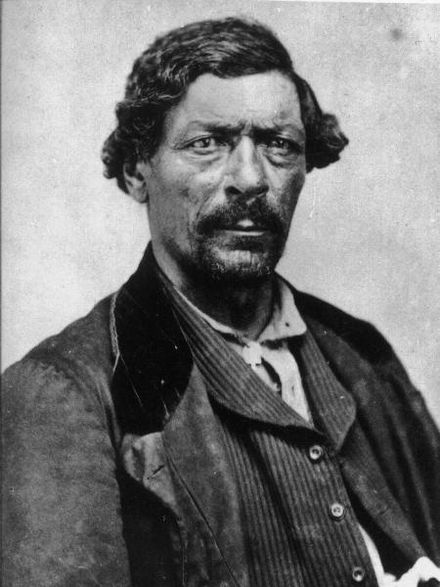

The leader of the rebellion, Jemmy, was a literate slave. In some reports, however, he is referred to as "Cato", and likely was held by the Cato, or Cater, family who lived near the Ashley River and north of the Stono River. He led 20 other enslaved Kongolese, who may have been former soldiers, in an armed march south from the Stono River. They were bound for Spanish Florida, where successive proclamations had promised freedom for fugitive slaves from British North America.

Jemmy and his group recruited nearly 60 other slaves and killed more than 20 whites before being intercepted and defeated by the South Carolina militia near the Edisto River. Survivors traveled another 30 miles before the militia finally defeated them a week later. Most of the captured slaves were executed; the surviving few were sold to markets in the West Indies. In response to the rebellion, the General Assembly passed the Negro Act of 1740, which restricted slaves' freedoms but improved working conditions and placed a moratorium on importing new slaves.

Since 1708, the majority of the population of the South Carolina colony were enslaved Africans, as importation of laborers from Africa had increased in recent decades with labor demand for the expansion of cotton and rice cultivation as commodity export crops. Historian Ira Berlin has called this the Plantation Generation, noting that South Carolina had become a "slave society," with slavery central to its economy. As planters had imported many slaves to satisfy the increased demand for labor, most slaves were Black Africans. Many in South Carolina were from the Kingdom of Kongo, which had converted to Catholicism in the 15th century. Numerous slaves had first been sold into slavery in the West Indies, where they were considered to become "seasoned" by working there under slavery, before being sold to South Carolina.

With the increase in slaves, colonists tried to regulate their relations, but there was always negotiation in this process. Slaves resisted by running away or initiating work slowdowns and revolts. At the time, Georgia was still an all-white colony, without slavery. South Carolina worked with Georgia to strengthen patrols on land and in coastal areas to prevent fugitives from reaching Spanish Florida. In the Stono case, the slaves may have been inspired by several factors to mount their rebellion. Spanish Florida offered freedom to fugitive slaves from the Southern Colonies; succesive governors in the colony had issued proclamations offering freedom for fugitive slaves in Florida in exchange for converting to Catholicism and serving for a period in the colonial militia. As a line of defense for Spanish Florida's largest settlement of St. Augustine, the settlement of Fort Mose was established by the colonial government to house fugitive slaves which had reached the colony. Stono was 150 miles (240 km) from the Florida line.

A malaria epidemic had recently killed many whites in Charleston, weakening the power of slaveholders. Lastly, historians have suggested the slaves organized their revolt to take place on Sunday, when planters would be occupied in church and might be unarmed. The Security Act of 1739 (which required all white males to carry arms even to church on Sundays) had been passed in August of that year in response to earlier runaways and minor rebellions, but it had not fully taken effect. Local officials were authorized to mount penalties against white men who did not carry arms after 29 September.

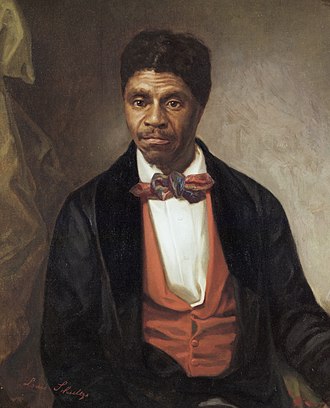

Jemmy, the leader of the revolt, was a literate slave described in an eyewitness account as "Angolan". Historian John K. Thornton has noted that he was more likely from the Kingdom of Kongo, as were the cohort of 20 slaves that joined him. The slaves were Catholic and some spoke Portuguese, both of which point to Kongo. A lengthy trade relationship with the Portuguese had led to the adoption of Catholicism and learning of the Portuguese language in the kingdom. The leaders of the Kingdom of Kongo had voluntarily converted in 1491, followed by their people; by the 18th century, the religion was a fundamental part of its citizens' identity. The nation had independent relations with Rome. Slavery was present in the region and it was regulated by Kongo.

Portuguese was the language of trade as well as one of the languages of educated people in Kongo. The Portuguese-speaking slaves in South Carolina were more likely to have learned about offers of freedom by Spanish agents. They would also have been attracted to the Catholicism of Spanish Florida. In the early 18th century, Kongo had been undergoing civil wars, leading to more people being captured and sold into slavery, including trained soldiers. It is likely that Jemmy and his rebel cohort were such military men, as they fought hard against the militia when they were caught, and were able to kill 20 men.

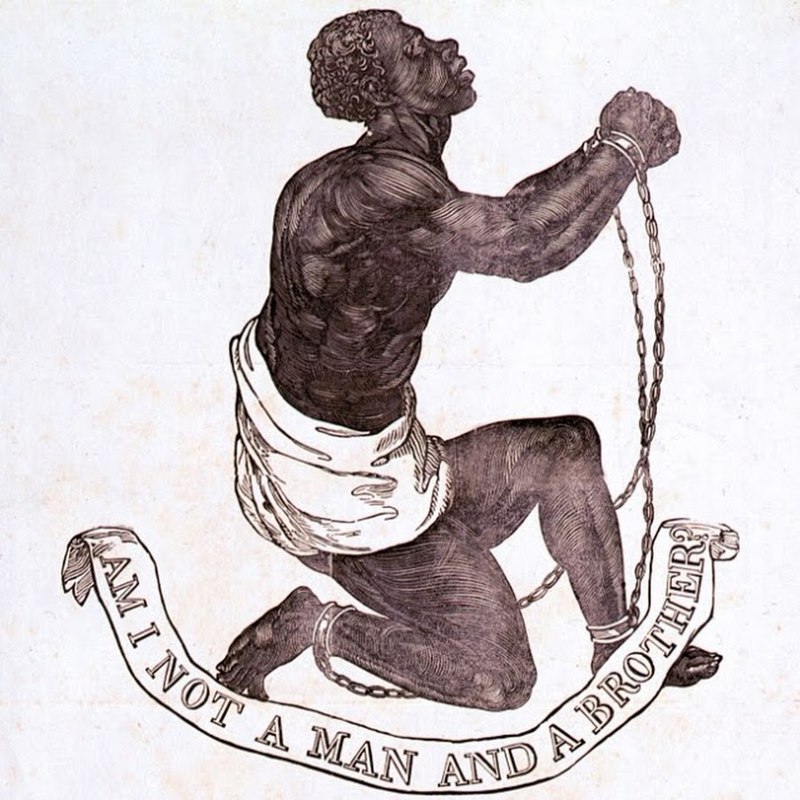

On Sunday, 9 September 1739, Jemmy gathered 22 enslaved Africans near the Stono River, 20 miles southwest of Charleston. Taking action on the day after the Feast of the Nativity of Mary connected their Catholic past with present purpose, as did the religious symbols they used. The Africans marched down the roadway with a banner that read "Liberty!", and chanted the same word in unison. They attacked Hutchenson's store at the Stono River Bridge, killing two storekeepers and seizing weapons and ammunition.

Raising a flag, the slaves proceeded south toward Spanish Florida, a well-known refuge for escapees.[3] On the way, they gathered more recruits, sometimes reluctant ones, for a total of 81. They burned six plantations and killed 23 to 28 whites along the way. While on horseback, South Carolina's Lieutenant Governor William Bull and five of his friends came across the group; they quickly went off to warn other slaveholders. Rallying a militia of planters and minor slaveholders, the colonists traveled to confront Jemmy and his followers.

The next day, the well-armed and mounted militia, numbering 19–99 men, caught up with the group of 76 slaves at the Edisto River. In the ensuing confrontation, 23 whites and 47 slaves were killed. While the slaves lost, they killed proportionately more whites than was the case in later rebellions. The colonists mounted the severed heads of the rebels on stakes along major roadways to serve as warning for other slaves who might consider revolt. The lieutenant governor hired Chickasaw and Catawba Indians and other slaves to track down and capture the Africans who had escaped from the battle. A group of the slaves who escaped fought a pitched battle with a militia a week later approximately 30 miles from the site of the first conflict. The colonists executed most of the rebellious slaves; they sold other slaves off to the markets of the West Indies.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed