By 1957, the NAACP had registered nine black students to attend the previously all-white Little Rock Central High, selected on the criteria of excellent grades and attendance.[2] Called the "Little Rock Nine", they were Ernest Green (b. 1941), Elizabeth Eckford (b. 1941), Jefferson Thomas (1942–2010), Terrence Roberts (b. 1941), Carlotta Walls LaNier (b. 1942), Minnijean Brown (b. 1941), Gloria Ray Karlmark (b. 1942), Thelma Mothershed (b. 1940), and Melba Pattillo Beals (b. 1941). Ernest Green was the first African American to graduate from Central High School.

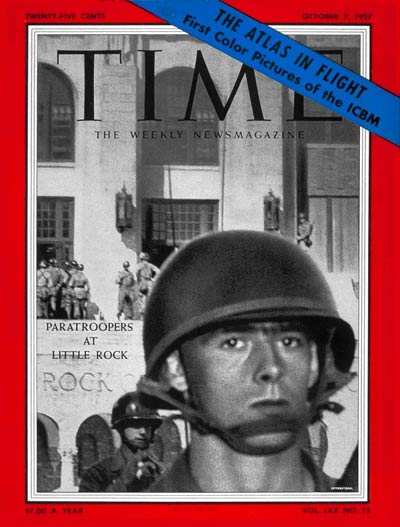

When integration began on September 4, 1957, the Arkansas National Guard was called in to "preserve the peace". Originally at orders of the governor, they were meant to prevent the black students from entering due to claims that there was "imminent danger of tumult, riot and breach of peace" at the integration. However, President Eisenhower issued Executive order 10730, which federalized the Arkansas National Guard and ordered them, as well as a detachment of the 101st Airborne Division stationed at Jacksonville, Arkansas, abut 10 miles from Little Rock. to support the integration on September 23 of that year, after which they protected the African American students, who became known in Civil Rights history as the Little Rock Nine.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed