Louisa Ann Swain

Louisa Ann Swain Born Louisa Ann Gardner, her father was lost at sea when she was young. Her mother then returned to her hometown of Charleston, South Carolina, but also died soon after. Orphaned at the age of 10, Swain was placed in the care of the Charleston Orphan House. In 1814, she and another girl were placed with a family as domestic servants for a period of four years, after which Swain was transferred to another family who requested specifically for her. She stayed with them until 1820, then moved to Baltimore where a year later she married Stephen Swain, who operated a chair factory. They had four children and in the 1830s, Stephen sold his business and the family moved, first to Zanesville, Ohio, and later to Richmond, Indiana. In 1869, the Swains moved to Laramie, Wyoming, to join their son Alfred.

On September 6, 1870, she arose early, put on her apron, shawl and bonnet, and walked downtown with a tin pail in order to purchase yeast from a merchant. She walked by the polling place and concluded she would vote while she was there. The polling place had not yet officially opened, but election officials asked her to come in and cast her ballot. She was described by a Laramie newspaper as "a gentle white-haired housewife, Quakerish in appearance". She was 69 years old when she cast the first ballot by any woman in the United States in a general election. Soon after the election, Stephen and Louisa Swain left Laramie and returned to Maryland to live near a daughter. Stephen died October 6, 1872, in Maryland. Louisa died January 25, 1880, in Lutherville, Maryland. She was buried in the Friends Burial Ground on Harford Road in Baltimore.

But how is it that Swain was able to cast this ballot -- and what's all this about women voting before 1807? Well. therein lie two tales. First, let's discuss Swain's historic vote. The true history of the American West has little to do with the image portray in popular films and TV shows, especially with respect to the role women played in the development of the west. What is more surprising to many is that the prominent role of women was not the result of the American ideal, but of Spanish Colonialism.

Under colonial Spain and newly independent Mexico, married women living in the borderlands of what is now the American Southwest had certain legal advantages not afforded their European-American peers. Under English common law, women, when they married, became feme covert (effectively dead in the eyes of the legal system) and thus unable to own property separately from their husbands. Conversely, Spanish-Mexican women retained control of their land after marriage and held one-half interest in the community property they shared with their spouses.

There were numerous landed women of note in the West. For example, María Rita Valdez operated Rancho Rodeo de las Aguas, now better known as a center of affluence and glamour: Beverly Hills. (Rodeo Drive takes its name from Rancho Rodeo.) After the U.S.-Mexican War, the del Valle family of Southern California held on to Rancho Camulos, and when Ygnacio, the patriarch, died, his widow Isabel and daughter Josefa successfully took over the ranch’s operations. Other successful entrepreneurs and property holders, who defended their interests in court when necessary, included San Francisco’s Juana Briones, Santa Fe’s Gertrudis Barceló, San Antonio-born María del Carmen Calvillo, and Phoenix’s Trinidad Escalante Swilling. In a frontier environment, they utilized the legal system to their advantage as women unafraid to exert their own authority.

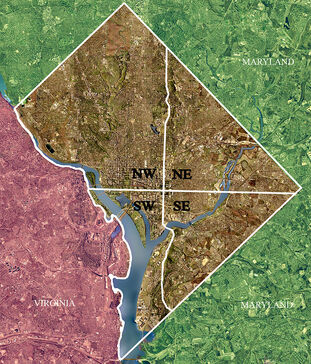

Because women were able to obtain wealth, they also gained political influence, thus it was that when Wyoming became an organized territory in 1869, among the innovations in its political system was suffrage for women -- or at least certain women. Wyoming’s law allowed certain women over the age of 21 to vote, own property, and serve in office. Women who wanted to cast a vote needed to prove they were seeking citizenship, a requirement that barred Native American and Chinese women from casting votes since at the time they legally could not become U.S. citizens. Black women were able to vote under this law, but it is unknown if any did and Wyoming had very few Black residents at the time. Wyoming’s territorial government had different reasons for granting women the right to vote: some thought it would attract more women to the sparsely populated territory while others thought that women played an important role on the frontier and had a right to decide how the territory should be run.

According to Laramie and Cheyenne newspapers, Swain became the first woman to legally cast a ballot since 1807 by 30 minutes. Swain’s vote beat that of Augusta C. Howe, the 27-year-old wife of the U.S. Marshall Church Howe of Cheyenne, Wyoming. At the time, however, the "since 1807" was not part of the story. Which brings us to the second tale -- the right of women to vote in New Jersey from 1776 to 1807.

No one knows whether New Jersey meant to do it. Later though, the state constitution’s signers made it clear they meant to keep it. In the summer of 1776, the colonies were about to collectively declare independence, and the Provincial Congress in Trenton was in a rush to write a state constitution. The state’s framers wrote and passed it in only five days. In the document, where it explains rules for elected officials, the governor is referred to as “he”; each assembly member, “he”; each county’s sheriff and its coroners, a “he.” But for some reason, when it describes the rules for the electorate, it says “they.” All inhabitants who are worth at least 50 pounds and have lived in New Jersey for a year, “they” shall have the right to vote.

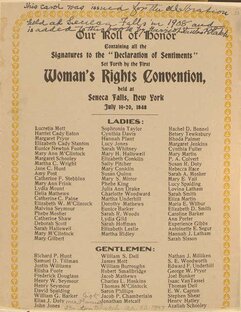

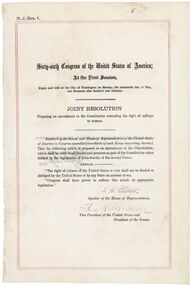

And that is how, for the first three decades of American independence, it was legal for some New Jersey women to vote, more than a century before the passage of the 19th Amendment. Even if it started out as an accidental loophole, a 1790 statute clarified that “they” meant “he or she” in seven New Jersey counties with large Quaker populations. In 1797, another statute expanded female suffrage from those counties to the entire state. For decades, there has been mostly anecdotal evidence that any women actually used this right — newspaper accounts complaining about women voting, and a copy of a poll list with two names that could have been women’s names, or men’s names incorrectly transcribed.

“This is the kind of detective work that historians love, because it’s an untold story,” said Philip Mead, chief historian at the Museum of the American Revolution in Philadelphia. Starting in 2018, museum staff led by curatorial fellow Marcela Micucci dug into the New Jersey State Archives, local historical societies and other cultural institutions looking for harder evidence. After months of searching, they hit pay dirt. "We found a poll list … from an election in Montgomery Township, Somerset County, in October of 1801. There were 343 voters on that list and 46 of them were women,” Micucci told The Washington Post. “I barged into [Mead’s] office, the list printed out in my hands, jumping up and down. It was very exciting.”

Since then, museum researchers have found 18 more poll lists, ranging from 1797 to 1807, nine of which contain women’s names. In total, they have identified 163 women who voted. “This was not just some women, but quite a substantial number of women,” Micucci said.

So how did New Jersey women lose the vote?

In a most American way — on the altar of partisan politics. By the time Washington left office in 1797, fights between the nascent political parties — the Federalists and the Democratic Republicans — were becoming so bitter that the first president spent much of his farewell address warning against them.

The situation worsened over the next decade, and with that came a rise in accusations of voter fraud. In 1802, political leaders in Hunterdon County urged the New Jersey legislature to overturn a local election, claiming some people on the poll lists were Philadelphia residents, immigrants, enslaved and, in particular, married women, Micucci said.

In 1806 in Essex County, women and people of color were blamed again when more votes were mysteriously cast than there were eligible voters. “This was a moment, in 1807, where Americans were having serious doubts about their democracy,” Mead said. “I think [legislators] were looking for a big action they could take to restore confidence in the voting system, and they crudely scapegoated women, people of color, immigrants.” The law was changed to remove the property requirement and limit the franchise to White men only.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed