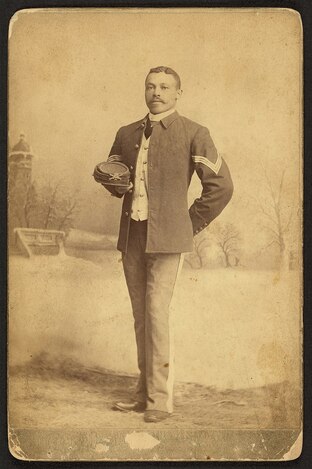

John Wesley Hardin

John Wesley Hardin Pursued by lawmen for most of his life, in 1877 at the age of 23, he was sentenced to 24 years in prison for murder. At the time of sentencing, Hardin claimed to have killed 42 men,[3] while contemporary newspaper accounts attributed 27 deaths to him.[4] While in prison, Hardin studied law and wrote an autobiography. He was well known for exaggerating or fabricating stories about his life and claimed credit for many killings that cannot be corroborated. Within a year of his 1894 release from prison, Hardin was killed by John Selman in an El Paso saloon.

Like many gunfighters and outlaws of the American West, it is difficult to separate fact from fiction in the mythology that has grown up around Hardin. Hardin was born in 1853 near Bonham, Texas to James "Gip" Hardin, a Methodist preacher and circuit rider, and Mary Elizabeth Dixson. He was named after John Wesley, the founder of the Methodist denomination of the Christian church. In his autobiography, Hardin described his mother as "blond, highly cultured . . [while] charity predominated in her disposition." Hardin was the second surviving son of ten children. In 1862, at age nine, Hardin tried to run away from home and join the Confederate army.

Hardin's father traveled over much of central Texas on his preaching circuit until he settled his family in Sumpter, Trinity County, Texas, in 1859. There, Hardin's father established and taught at the school that John Hardin and his siblings attended. In 1867 while attending his father's school, Hardin was taunted by another student, Charles Sloter. Sloter accused Hardin of being the author of graffiti on the schoolhouse wall that insulted a girl in his class. Hardin denied writing the poetry, claiming in turn that Sloter was the author. Sloter charged at Hardin with a knife, but Hardin stabbed him with his own knife, almost killing him. Hardin was nearly expelled over the incident.

Hardin first killed a man in 1868, a freedman who had been a salve of Hardin's uncle, again claiming self defense Fearing that his son would not receive a fair trial from the reconstruction government, Hardin's father encouraged him to become a fugitive. When his hideout was betrayed, Hardin ambushed an killed three soldiers sent to arrest him. Hardin then roamed west Texas using aliases and occasionally holding honest professions, but eventually he would engage in some act of violence that required him to again flee.

In January 1871, Hardin was arrested for the murder of Waco, Texas, city marshal Laban John Hoffman; however, he denied committing this crime. Hardin procured a pistol and killed one of the men escorting him to Waco for trial. Hardin again claimed that he acted in self defense when the man started to beat him. Hardin later claimed to have been taken into custody by three men, probably bounty hunters, killing them all when they became "drunk and careless."

Hardin turned to cattle rustling, often working as a legitimate cowboy, even claiming to have been made a trial boss. Hardin crossed paths with J.B. "Wild Bill" Hickok. Respecting Hickok as a shootist, if not a lawman, Hardin was alleged to have told an acquaintance who tried to incite Hardin to kill the Marshall, "If Bill needs killing why don't you kill him yourself?" Nonetheless, Hardin confronted Hickok when the latter attempted to enforce the town ordinance that barred wearing guns within the town. When ordered to turn over his weapons, Hardin reached down, picked his revolvers up from the holsters, and handed the guns to Wild Bill butts forward, then swiftly rolled them over in his hands and suddenly Wild Bill was staring right into their muzzles. However, both men did back down. Hickok had no knowledge that Hardin was a wanted man, and he advised Hardin to avoid problems while in Abilene.

Hardin met up with Hickok again while on a cattle drive in August 1871. This time, Hickok allowed Hardin to carry his pistols into town - something he had never allowed others to do. For his part, Hardin (still using his alias of Wesley "Little Arkansaw" Clemmons") was fascinated by Wild Bill and reveled in being seen on intimate terms with such a celebrated gunfighter.

On August 6, 1871, Hardin, his cousin Gip Clements, and a rancher friend named Charles Couger put up for the night at the American House Hotel after an evening of gambling. Clements and Hardin shared one room, with Couger in the adjacent room. All three had been drinking heavily. Sometime during the evening, Hardin was awakened by loud snoring coming from Couger's room. He first shouted several times for the man to "rollover" and then, irritated by the lack of response, drunkenly fired several bullets through the shared wall, in an apparent effort to awaken him. Couger was hit in the heart by one of the bullets as he lay in bed and was killed instantly. Although Hardin may not have intended to kill Couger, he had violated an ordinance prohibiting firing a gun within the city limits. Half-dressed and still drunk, he and Clements exited through a second-story window onto the roof of the hotel. He saw Hickok arrive with four policemen. "Now, I believed," Hardin wrote, "that if Wild Bill found me in a defenseless condition he would take no explanation, but would kill me to add to his reputation."

A newspaper reported, "A man was killed in his bed at a hotel in Abilene, Monday night, by a desperado called 'Arkansas'. The murderer escaped. This was his sixth murder." Hardin leapt from the roof into the street and hid in a haystack for the rest of the night. He then stole a horse and rode to a cow camp 35 miles outside town. Hardin claimed he ambushed lawman Tom Carson and two other deputies there. According to Hardin, he did not kill them but forced them to remove all their clothing and walk back to Abilene. The next day, Hardin left for Texas, never to return to Abilene.

Over the next four years Hardin became involved in different criminal intrigues including being a participant in the Sutton-Taylor feud through his relationship to the Taylors. Having married and after having been seriously wounded in the feud, Hardin sought to "clear his slate" and surrendered to local authorities. However, upon learning that he would be charged with many murders and likely would hang, he escaped jail.

Relocating briefly to Florida, Hardin, then just 21, assumed a new alias and returned to Texas in an effort to settle with his wife and newborn daughter. However, the ongoing feud again involved Hardin in more violence including the killing, again allegedly in self-defense, of Brown County Deputy Sheriff Charles Webb . Vigilantes lynched several of Hardin's relatives and his wife and parents were arrested, allegedly for their own protection, but more likely in an effort to force Hardin to surrender.

On January 20, 1875, the Texas Legislature authorized Governor Richard B. Hubbard to offer a $4,000 reward for Hardin's arrest. An undercover Texas Ranger named Jack Duncan intercepted a letter sent to Hardin's father-in-law by Hardin's brother-in-law, Joshua Robert "Brown" Bowen. The letter mentioned that Hardin was hiding out on the Alabama-Florida border using the name "James W. Swain". In his autobiography, Hardin admitted that he had "adopted" this alias from Brenham, Texas, Town Marshal Henry Swain, who had married a cousin of Hardin's named Molly Parks.

In March 1876, Hardin wounded a man, in Florida, who had tried to mediate a quarrel between him and another man. In November 1876, in Mobile, Alabama, Hardin was arrested briefly for having marked cards. In mid-1877, two former slaves of his father's, "Jake" Menzel and Robert Borup tried to capture Hardin in Gainesville, Florida. Hardin killed one and blinded the other.

On August 24, 1877, Rangers and local authorities confronted Hardin on a train in Pensacola, Florida. He attempted to draw a .44 Colt cap-and-ball pistol but it got caught up in his suspenders. The officers knocked Hardin unconscious. They arrested two of his companions, and Ranger John B. Armstrong killed a third, a man named Mann, who had a pistol in his hand. Hardin claimed that he was captured while smoking his pipe and that Duncan only found Hardin's pistol under his shirt after his arrest.

Hardin was tried for Webb's killing, and on June 5, 1878, was sentenced to serve 25 years in Huntsville Prison. In 1879, Hardin and 50 other convicts were stopped within hours of successfully tunneling into the prison armory. Hardin made several attempts to escape. On February 14, 1892, during his prison term, he was convicted of another manslaughter charge for the earlier shooting of J.B. Morgan and given a two-year sentence to be served concurrently with his unexpired 25-year sentence.

Hardin eventually adapted to prison life. While there, he read theological books, becoming the superintendent of the prison Sunday School, and studied law. He was plagued by recurring poor health, especially when wounds he had received became re-infected in 1883, causing him to be bedridden for almost two years. In 1892, Hardin was described as 5.9 feet (1.8 m) tall and 160 pounds (73 kg), with a fair complexion, hazel eyes, dark hair, and wound scars on his right knee, left thigh, right side, hip, elbow, shoulder, and back. On November 6, 1892, during Hardin's stay in prison, his first wife, Jane, died.

While in prison, he wrote an autobiography. He was well known for wildly exaggerating, or completely making up, stories about his life. He claimed credit for many murders that cannot be corroborated. Hardin wrote that he was first exposed to violence in 1861 when he saw a man named Turner Evans stabbed by John Ruff. Evans died of his injuries and Ruff was jailed. Hardin wrote, "... Readers you see what drink and passion will do. If you wish to be successful in life, be temperate and control your passions; if you don't, ruin and death is the result."

On February 17, 1894, Hardin was released from prison, having served seventeen years of his twenty-five-year sentence. He was forty years old when he returned to Gonzales, Texas. Later that year, on March 16, Hardin was pardoned, and, on July 21, he passed the state's bar examination, obtaining his license to practice law. According to a newspaper article in 1900, shortly after being released from prison, Hardin committed negligent homicide when he made a $5 bet that he could "at the first shot" knock a Mexican man off the soapbox on which the man was "sunning" himself, winning the bet and leaving the man dead from the fall and not the gunshot.

On January 9, 1895, Hardin married a 15-year-old girl named Callie Lewis. The marriage ended quickly, although it was never legally dissolved. Afterward, Hardin moved to El Paso, Texas. An El Paso lawman, John Selman Jr. arrested Hardin's acquaintance and part-time prostitute, the "widow" M'Rose (or Mroz), for "brandishing a gun in public". Hardin confronted Selman and the two men argued. Some accounts state that Hardin pistol-whipped the younger man. Selman's 56-year-old father, Constable John Selman Sr. (himself a notorious gunman and former outlaw), approached Hardin on the afternoon of August 19, 1895, and the two men exchanged heated words.

That night, Hardin went to the Acme Saloon where he began playing dice. Shortly before midnight, Selman Sr. entered the saloon, walked up to Hardin from behind, and shot him in the head, killing him instantly. As Hardin lay on the floor, Selman fired three more shots into him. Hardin was buried the following day in Concordia Cemetery, in El Paso.

Selman Sr. was arrested for murder and stood trial. He claimed self-defense, stating that he witnessed Hardin attempting to draw his pistol upon seeing him enter the saloon, and a hung jury resulted in his being released on bond, pending a retrial. However, before the retrial could be organized Selman was killed in a shootout with US Marshal George Scarborough on April 6, 1896, during an argument following a card game.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed