Open Casket at Emmett Till's funeral in Chicago

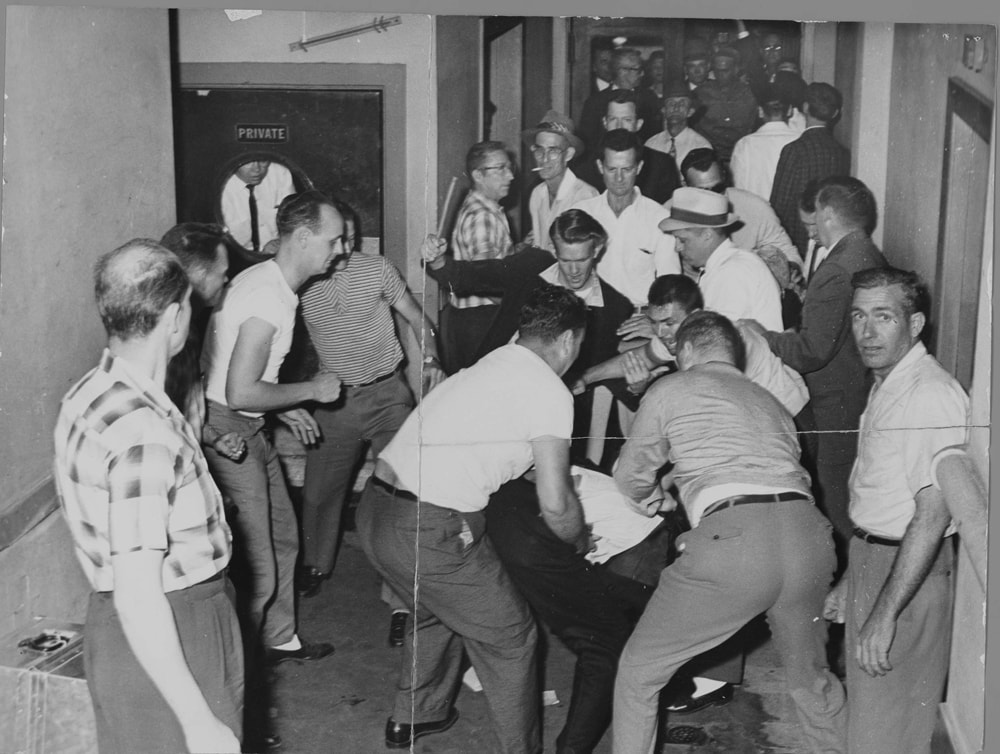

Open Casket at Emmett Till's funeral in Chicago Till was born and raised in Chicago, Illinois. During summer vacation in August 1955, he was visiting relatives near Money, Mississippi, in the Mississippi Delta region. He spoke to 21-year-old Carolyn Bryant, the white married proprietor of a small grocery store there. Although what happened at the store is a matter of dispute, Till was accused of flirting with or whistling at Bryant. Till's interaction with Bryant, perhaps unwittingly, violated the unwritten code of behavior for a black male interacting with a white female in the Jim Crow-era South. Several nights after the incident in the store, Bryant's husband Roy and his half-brother J.W. Milam were armed when they went to Till's great-uncle's house and abducted Emmett. They took him away and beat and mutilated him, before shooting him in the head and sinking his body in the Tallahatchie River. Three days later, Till's body was discovered and retrieved from the river.

Till's body was returned to Chicago where his mother insisted on a public funeral service with an open casket which was held at Roberts Temple Church of God in Christ. It was later said that "The open-coffin funeral held by Mamie Till Bradley exposed the world to more than her son Emmett Till's bloated, mutilated body. Her decision focused attention not only on U.S. racism and the barbarism of lynching but also on the limitations and vulnerabilities of American democracy". Tens of thousands attended his funeral or viewed his open casket, and images of his mutilated body were published in black-oriented magazines and newspapers, rallying popular black support and white sympathy across the U.S. Intense scrutiny was brought to bear on the lack of black civil rights in Mississippi, with newspapers around the U.S. critical of the state. Although local newspapers and law enforcement officials initially decried the violence against Till and called for justice, they responded to national criticism by defending Mississippians, temporarily giving support to the killers.

In September 1955, an all-white jury found Bryant and Milam not guilty of Till's murder. Protected against double jeopardy, the two men publicly admitted in a 1956 interview with Look magazine that they had killed Till. Till's murder was seen as a catalyst for the next phase of the civil rights movement. In December 1955, the Montgomery bus boycott began in Alabama and lasted more than a year, resulting eventually in a U.S. Supreme Court ruling that segregated buses were unconstitutional. According to historians, events surrounding Emmett Till's life and death continue to resonate. An Emmett Till Memorial Commission was established in the early 21st century. The Sumner County Courthouse was restored and includes the Emmett Till Interpretive Center. Fifty-one sites in the Mississippi Delta are memorialized as associated with Till.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed