Although Nixon's actions did not formally abolish the existing Bretton Woods system of international financial exchange, the suspension of one of its key components effectively rendered the Bretton Woods system inoperative. While Nixon publicly stated his intention to resume direct convertibility of the dollar after reforms to the Bretton Woods system had been implemented, all attempts at reform proved unsuccessful. By 1973, the Bretton Woods system was replaced de facto by the current regime based on freely floating fiat currencies.

In 1944, representatives from 44 nations met in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire to develop a new international monetary system that came to be known as the Bretton Woods system. Conference attendees had hoped that this new system would "ensure exchange rate stability, prevent competitive devaluations, and promote economic growth". It was not until 1958 that the Bretton Woods system became fully operational. Countries now settled their international accounts in dollars that could be converted to gold at a fixed exchange rate of $35 per ounce, which was redeemable by the U.S. government. Thus, the United States was committed to backing every dollar overseas with gold, and other currencies were pegged to the dollar.

For the first years after World War II, the Bretton Woods system worked well. With the Marshall Plan, Japan and Europe were rebuilding from the war, and countries outside the US wanted dollars to spend on American goods—cars, steel, machinery, etc. Because the U.S. owned over half the world's official gold reserves—574 million ounces at the end of World War II—the system appeared secure.

However, from 1950 to 1969, as Germany and Japan recovered, the US share of the world's economic output dropped significantly, from 35% to 27%. Furthermore, a negative balance of payments, growing public debt incurred by the Vietnam War, and monetary inflation by the Federal Reserve caused the dollar to become increasingly overvalued in the 1960s.

In France, the Bretton Woods system was called "America's exorbitant privilege" as it resulted in an "asymmetric financial system" where non-US citizens "see themselves supporting American living standards and subsidizing American multinationals". As American economist Barry Eichengreen summarized: "It costs only a few cents for the Bureau of Engraving and Printing to produce a $100 bill, but other countries had to pony up $100 of actual goods in order to obtain one". In February 1965 President Charles de Gaulle announced his intention to exchange its U.S. dollar reserves for gold at the official exchange rate.

By 1966, non-US central banks held $14 billion, while the United States had only $13.2 billion in gold reserve. Of those reserves, only $3.2 billion was able to cover foreign holdings as the rest was covering domestic holdings.

By 1971, the money supply had increased by 10%. In May 1971, West Germany left the Bretton Woods system, unwilling to revalue the Deutsche Mark. In the following three months, this move strengthened its economy. Simultaneously, the dollar dropped 7.5% against the Deutsche Mark. Other nations began to demand redemption of their dollars for gold. Switzerland redeemed $50 million in July. France acquired $191 million in gold. On August 5, 1971, the United States Congress released a report recommending devaluation of the dollar, in an effort to protect the dollar against "foreign price-gougers". On August 9, 1971, as the dollar dropped in value against European currencies, Switzerland left the Bretton Woods system. The pressure began to intensify on the United States to leave Bretton Woods.

At the time, the U.S. also had an unemployment rate of 6.1% (August 1971) and an inflation rate of 5.84% (1971).

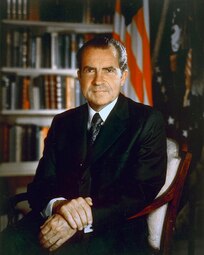

To combat these problems, President Nixon consulted Federal Reserve chairman Arthur Burns, incoming Treasury Secretary John Connally, and then Undersecretary for International Monetary Affairs and future Fed Chairman Paul Volcker.

On the afternoon of Friday, August 13, 1971, these officials along with twelve other high-ranking White House and Treasury advisors met secretly with Nixon at Camp David. There was great debate about what Nixon should do, but ultimately Nixon, relying heavily on the advice of the self-confident Connally, decided to break up Bretton Woods by announcing the following actions on August 15:

- Nixon directed Treasury Secretary Connally to suspend, with certain exceptions, the convertibility of the dollar into gold or other reserve assets, ordering the gold window to be closed such that foreign governments could no longer exchange their dollars for gold.

- Nixon issued Executive Order 11615 (pursuant to the Economic Stabilization Act of 1970), imposing a 90-day freeze on wages and prices in order to counter inflation. This was the first time the U.S. government had enacted wage and price controls since World War II.

- An import surcharge of 10 percent was set to ensure that American products would not be at a disadvantage because of the expected fluctuation in exchange rates.

Speaking on television on Sunday, August 15, when American financial markets were closed, Nixon said the following:

The third indispensable element in building the new prosperity is closely related to creating new jobs and halting inflation. We must protect the position of the American dollar as a pillar of monetary stability around the world.

In the past 7 years, there has been an average of one international monetary crisis every year ...

I have directed Secretary Connally to suspend temporarily the convertibility of the dollar into gold or other reserve assets, except in amounts and conditions determined to be in the interest of monetary stability and in the best interests of the United States.

Now, what is this action—which is very technical—what does it mean for you?

Let me lay to rest the bugaboo of what is called devaluation.

If you want to buy a foreign car or take a trip abroad, market conditions may cause your dollar to buy slightly less. But if you are among the overwhelming majority of Americans who buy American-made products in America, your dollar will be worth just as much tomorrow as it is today.

The effect of this action, in other words, will be to stabilize the dollar.

The American public believed the government was rescuing them from price gougers and from a foreign-caused exchange crisis. Politically, Nixon's actions were a great success. The Dow rose 33 points the next day, its biggest daily gain ever at that point, and the New York Times editorial read, "We unhesitatingly applaud the boldness with which the President has moved." By December 1971, the import surcharge was dropped as part of a general revaluation of the Group of Ten (G-10) currencies, which under the Smithsonian Agreement were thereafter allowed 2.25% devaluations from the agreed exchange rate. In March 1973, the fixed exchange rate system became a floating exchange rate system. The currency exchange rates no longer were governments' principal means of administering monetary policy.

The Nixon Shock has been widely considered to be a political success, but an economic mixed bag in bringing on the stagflation of the 1970s and leading to the instability of floating currencies. The dollar plunged by a third during the 1970s. According to the World Trade Review's report "The Nixon Shock After Forty Years: The Import Surcharge Revisited", Douglas Irwin reports that for several months, U.S officials could not get other countries to agree to a formal revaluation of their currencies. The German Mark appreciated significantly after it was allowed to float in May 1971. Further, the Nixon Shock unleashed enormous speculation against the dollar. It forced Japan's central bank to intervene significantly in the foreign exchange market to prevent the yen from increasing in value. Within two days August 16–17, 1971, Japan's central bank had to buy $1.3 billion to support the dollar and keep the yen at the old rate of ¥360 to the dollar. Japan's foreign exchange reserves rapidly increased: $2.7 billion (30%) a week later and $4 billion the following week. Still, this large-scale intervention by Japan's central bank could not prevent the depreciation of US dollar against the yen. France also was willing to allow the dollar to depreciate against the franc, but not allow the franc to appreciate against gold. Even much later, in 2011, Paul Volcker expressed regret over the abandonment of Bretton Woods: "Nobody's in charge," Volcker said. "The Europeans couldn't live with the uncertainty and made their own currency and now that's in trouble."

Debates over the Nixon Shock have persisted to the present day, with economists and politicians across the political spectrum trying to make sense of the Nixon Shock and its impact on monetary policy in the light of the financial crisis of 2007–2008.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed