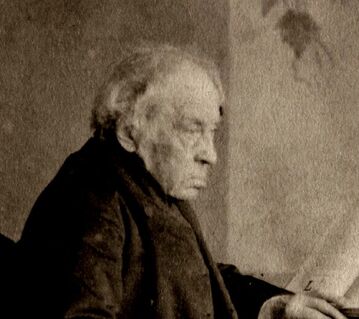

Henry Phillpotts, the Anglican Bishop of Exeter was one of the most vocal opponents of the Marriage Act of 1836 which extended religious freedom in the United Kingdom by recognizing marriages performed in non-Anglican churches

Henry Phillpotts, the Anglican Bishop of Exeter was one of the most vocal opponents of the Marriage Act of 1836 which extended religious freedom in the United Kingdom by recognizing marriages performed in non-Anglican churches Historically, the law of marriage developed differently in Scotland to other jurisdictions in the United Kingdom as a consequence of the differences in Scots law and role of the separate established Church of Scotland. These differences led to a tradition of couples from England and Wales eloping to Scotland, most famously to marry at border towns such as Gretna Green.

The Clandestine Marriages Act 1753, long title "An Act for the Better Preventing of Clandestine Marriage", popularly known as Lord Hardwicke's Marriage Act (citation 26 Geo. II. c. 33), was the first statutory legislation in England and Wales to require a formal ceremony of marriage. It came into force on 25 March 1754. The Act was precipitated by a dispute about the validity of a Scottish marriage, although pressure to address the problem of clandestine marriage had been growing for some time.

The difficulty with the Clandestine Marriages Act was that it formalized as law the practice recognizing only marriages performed in Church of England parishes, Jewish Temples, and, in recognition of the growing influence of the Society of Friends, "Quaker marriage," it also rendered marriages in Catholic and dissenter (i.e. Protestant) churches and those of all other non-Christian ceremonies as not legally recognized. It also did not end the practice of Scottish marriage because it's effect was to legitimize marriages performed in Scotland in accord with Scot's law.

Another aspect of the law that was unpopular was that it imposed punishments on the clergyman who performed a marriage that did not comport with the law. A similar act in the Isle of Man (an independent state also ruled by the English monarch) punished clergy from abroad, who were convicted of conducting marriages in breach of the Manx Marriage Act's requirements to be pilloried and have their ears cropped, before being imprisoned, fined and deported.

The result was that in order to have a "legal" marriage - a new concept at the time - required many couples, especially Catholics, to marry twice, once in their own faith ceremony, and again in a perfunctory ceremony performed by a Church of England clergyman. When asked why the Catholic Church was recommending that its parishioners marry in an Anglican church, one priest "declared gloomily that almost every day the wife of an Irish laborer was deserted by her husband and could get no redress" through the courts because the marriage was not legal.

The Marriage Act 1836, adopted on August 17, 1836, allowed marriages to be legally registered in buildings belonging to other religious groups. Religious groups could apply for registration for their buildings with the Registrar General and subsequently could conduct weddings if a Registrar and two witnesses were present.

The Act was not without its critics, however. One of the most vocal opponents of the bill was Henry Phillpotts, the Anglican Bishop of Exeter. The Times of 13 October 1836 reports that he denounced the bill as being "a disgrace to British legislation. [It] is pretended to be called for to prevent clandestine marriages, but I think it will greatly facilitate such proceedings. Not solemnized by the church of England, may be celebrated without entering into a consecrated building, may be contracted by anybody, and will be equally valid, whether it takes place in the house of God, or in the house of a registering clerk, one of the lowest functionaries of the state. The parties may take one another for better and for worse, without calling God to witness their plighted troth. No blessing sought; no solemn vows of mutual fidelity; no religious solemnity whatever."

RSS Feed

RSS Feed