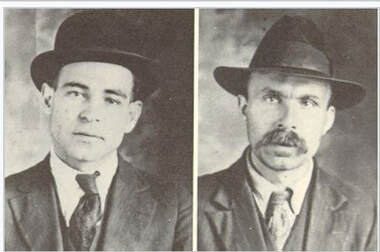

Sacco and Vanzetti

Sacco and Vanzetti Sacco and Vanzetti were Italian immigrant who were controversially accused of murdering Parmenter and Beradelli, a guard and a paymaster, during the April 15, 1920, armed robbery of the Slater and Morrill Shoe Company in Braintree, Massachusetts. The police investigation immediately focused on the Italian immigrant community of the Boston area, giving particular attention to members of the anarchist movement. The investigation ultimately settled on an anarchist cell of which Sacco and Vanzetti were members.

Although there was significant evidence that the robbery was part of a broader scheme of violent criminal acts by anarchists to finance their revolutionary goals, evidence that the cell in which Sacco and Vanzetti were action was scant. Nonetheless, the two were arrested and indicted for the robbery and murders; Vanzetti was also charged with another robbery that had occurred in Bridgewater, Massachusetts, shortly before the Braintree Robbery. Following their arrest, a series of anarchist attacks were carried out; however, it is generally conceded that these were merely a response to the arrest of anyone associated with the movement.

Vanzetti was convicted on the Bridgewater robbery despite discrepancies in the testimony of the state's witnesses and the presentation of numerous alibi witnesses. It is generally accepted that the jury disregarded the alibi witnesses' testimony because they were all of Italian descent.

Sacco and Vanzetti went on trial May 21, 1921, at Dedham, Norfolk County for the Braintree robbery and murders. Webster Thayer, the judge in the Bridgewater trial, again presided; he had asked to be assigned to the trial. Frederick G. Katzmann prosecuted for the State. Thayer and and Katzmann were vocal opponents of immigrants and "political radicals."

Vanzetti was represented by brothers Jeremiah and Thomas McAnraney. Sacco was represented by Fred H. Moore and William J. Callahan. The choice of Moore, a former attorney for the Industrial Workers of the World, proved a key mistake for the defense. A notorious radical from California, Moore quickly enraged Judge Thayer with his courtroom demeanor, often doffing his jacket and once, his shoes. Reporters covering the case heard Judge Thayer, during a lunch recess, proclaim, "I'll show them that no long-haired anarchist from California can run this court!" and later, "You wait till I give my charge to the jury. I'll show them." Throughout the trial, Moore and Thayer clashed repeatedly over procedure and decorum.

There was almost no direct evidence implicating the two men, however circumstantial evidence, including forensic evidence that was subsequently question for its accuracy, was again set against the alibi testimony of immigrant Italian witnesses. After a few hours' deliberation on July 14, 1921, the jury convicted Sacco and Vanzetti of first-degree murder and they were sentenced to death by the trial judge. Anti-Italianism, anti-immigrant, and anti-Anarchist bias were suspected as having heavily influenced the verdict.

A series of appeals followed, funded largely by the private Sacco and Vanzetti Defense Committee. The appeals were based on recanted testimony, conflicting ballistics evidence, a prejudicial pretrial statement by the jury foreman, and a confession by an alleged participant in the robbery. All appeals were denied by trial judge Webster Thayer and also later denied by the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court. By 1926, the case had drawn worldwide attention. As details of the trial and the men's suspected innocence became known, Sacco and Vanzetti became the center of one of the largest causes célèbres in modern history. In 1927, protests on their behalf were held in every major city in North America and Europe, as well as in Tokyo, Sydney, Melbourne, São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, Buenos Aires, Dubai, Montevideo, Johannesburg, and Auckland.

Celebrated writers, artists, and academics pleaded for their pardon or for a new trial. Harvard law professor and future Supreme Court justice Felix Frankfurter argued for their innocence in a widely read Atlantic Monthly article that was later published in book form. The two were scheduled to die in April 1927, accelerating the outcry. Responding to a massive influx of telegrams urging their pardon, Massachusetts governor Alvan T. Fuller appointed a three-man commission to investigate the case. After weeks of secret deliberation that included interviews with the judge, lawyers, and several witnesses, the commission upheld the verdict. Sacco and Vanzetti were executed in the electric chair just after midnight on August 23, 1927.

Investigations in the aftermath of the executions continued throughout the 1930s and 1940s. The publication of the men's letters, containing eloquent professions of innocence, intensified belief in their wrongful execution. Additional ballistics tests and incriminating statements by the men's acquaintances have clouded the case. On August 23, 1977—the 50th anniversary of the executions—Massachusetts Governor Michael Dukakis issued a proclamation that Sacco and Vanzetti had been unfairly tried and convicted and that "any disgrace should be forever removed from their names". Later analyses have also added doubt to their culpability in the crimes for which they were convicted.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed