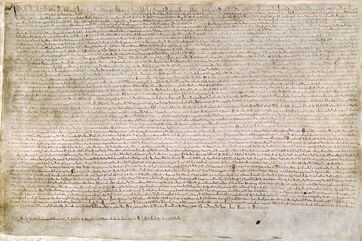

Although many of the ideas expressed in Magna Carta are similar or identical to modern concepts of liberal democracy - trial by jury, no taxation without consent of the governed, the government is subject to the law, etc. - the fact is that Magna Carta was imposed on King John by the English barons at Runnymede under duress. As soon as the barons had returned to their estates and, more importantly, most, but not all, had disbanded their retinues of knights and men-at-arms, John set about undoing what had been done.

His first act was to send an emissary to the Vatican, seeking to have Pope Clement III declare Magna Carta to be contrary to God's will. John had good reason to hope that the Pope would respond positively to this entreaty.

Magna Carta had not appeared full born on June 15, 2025, but was the process of a years long process of negotiation during which John sought to delay having to make any concessions to the barons while gather international support. During these negotiations, it was John's hope that the Pope would give him valuable legal and moral support, and accordingly John played for time; the King had declared himself to be a papal vassal in 1213 and correctly believed he could count on the Pope for help. John also began recruiting mercenary forces from France, although some were later sent back to avoid giving the impression that the King was escalating the conflict. In a further move to shore up his support, John took an oath to become a crusader, a move which gave him additional political protection under church law, even though many felt the promise was insincere.

Letters backing John arrived from the Pope in April 2015, but by then the rebel barons had organized into a military faction. They congregated at Northampton in May and renounced their feudal ties to John, marching on London, Lincoln, and Exeter. John's efforts to appear moderate and conciliatory had been largely successful, but once the rebels held London, they attracted a fresh wave of defectors from the royalists. The King offered to submit the problem to a committee of arbitration with the Pope as the supreme arbiter, but this was not attractive to the rebels. Stephen Langton, the archbishop of Canterbury, had been working with the rebel barons on their demands, and after the suggestion of papal arbitration failed, John instructed Langton to organize peace talks. The result was the great gathering at Runnymede and the sealing (not signing, as is often incorrectly stated) of Magna Carta.

Having failed at obtaining Papal arbitration, John simply requested that the Pope declare the charter to be null and void. Clement, who viewed any surrender of power by a temporal ruler to be a challenge to the Church's own power, obliged. In fact, Clement had dispatched commissioners even before John's request was received who arrived in England and promptly excommunicated the barons who had refused to disband their forces. Once aware of the charter, the Pope responded in detail: in a letter dated 24 August and arriving in late September, he declared the charter to be "not only shameful and demeaning but also illegal and unjust" since John had been "forced to accept" it, and accordingly the charter was "null, and void of all validity for ever"; under threat of excommunication, the King was not to observe the charter, nor the barons try to enforce it.

By then, however, violence had broken out between the two sides; less than three months after it had been agreed, John and the loyalist barons firmly repudiated the failed charter: the First Barons' War erupted. The rebel barons concluded that peace with John was impossible, and turned to Philip II's son, the future Louis VIII, for help, offering him the English throne. The war soon settled into a stalemate. The King became ill and died on the night of 18 October 1216, leaving the nine-year-old Henry III as his heir.

Although the Charter of 1215 was a failure as a peace treaty, it was resurrected under the new government of the young Henry III as a way of drawing support away from the rebel faction. On his deathbed, King John appointed a council of thirteen executors to help Henry reclaim the kingdom, and requested that his son be placed into the guardianship of William Marshal, one of the most famous knights in England. William knighted the boy, and Cardinal Guala Bicchieri, the papal legate to England, then oversaw his coronation at Gloucester Cathedral on 28 October.

It would not be until 1217 that peace was nominally restored in England with Henry confirmed on the throne and a modified version of the Charter adopted (but only occasionally and inconsistently adhered to). The primary reason the conflict ended was the real concern that Louis would gain the throne of England and, in effect, incorporate the nation into a larger French state once he succeeded to that throne, without any guarantee concessions. The rebel barons began to defect to Henry when they realized that they might have to face a powerful, perhaps indomitable, French monarch rather than a relatively weak English one still in his minority.

Thus, while many of the principles set out in Magna Carta were subsequently repeated and enhanced in subsequent documents and eventually adopted as formal laws, the Great Charter was, essentially, a failure in that it neither produced the hoped for peace nor resulted in more than a token acceptance by King John. The Pope's declaration that the Charter was null and void was never "reversed" by any authority - Magna Carta effectively ceased to be enforceable on August 24, 2015, two months and nine days after it was sealed.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed