The Declaration was originally drafted by the Marquis de Lafayette, in consultation with Thomas Jefferson. Influenced by the doctrine of "natural right", the rights of man are held to be universal: valid at all times and in every place. It became the basis for a nation of free individuals protected equally by the law. It is included in the beginning of the constitutions of both the Fourth French Republic (1946) and Fifth Republic (1958) and is still current. Inspired by Enlightenment philosophers, the Declaration was a core statement of the values of the French Revolution and had a major impact on the development of popular conceptions of individual liberty and democracy in Europe and worldwide.

The 1789 Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, together with the 1215 Magna Carta, the 1689 English Bill of Rights, the 1776 United States Declaration of Independence, and the 1789 United States Bill of Rights, inspired, in large part, the 1948 United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

The content of the document emerged largely from the ideals of the Enlightenment. The principal drafts were prepared by Lafayette, working at times with his close friend Thomas Jefferson. In August 1789, the Abbé Emmanuel Joseph Sieyès and Honoré Mirabeau played a central role in conceptualizing and drafting the final Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen.

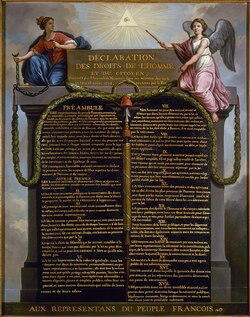

The last article of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen was adopted on the 26 of August 1789 by the National Constituent Assembly, during the period of the French Revolution, as the first step toward writing a constitution for France. Inspired by the Enlightenment, the original version of the Declaration was discussed by the representatives on the basis of a 24 article draft proposed by the sixth bureau led by Jérôme Champion de Cicé. The draft was later modified during the debates. A second and lengthier declaration, known as the Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen of 1793, was written in 1793 but never formally adopted.

The concepts in the Declaration come from the philosophical and political duties of the Enlightenment, such as individualism, the social contract as theorized by the Genevan philosopher Rousseau, and the separation of powers espoused by the Baron de Montesquieu. As can be seen in the texts, the French declaration was heavily influenced by the political philosophy of the Enlightenment and principles of human rights as was the U.S. Declaration of Independence which preceded it.

The declaration defines a single set of individual and collective rights for all men. Influenced by the doctrine of natural rights, these rights are held to be universal and valid in all times and places. For example, "Men are born and remain free and equal in rights. Social distinctions may be founded only upon the general good." They have certain natural rights to property, to liberty, and to life. According to this theory, the role of government is to recognize and secure these rights. Furthermore, the government should be carried on by elected representatives.

At the time it was written, the rights contained in the declaration were only awarded to men. Furthermore, the declaration was a statement of vision rather than reality. The declaration was not deeply rooted in either the practice of the West or even France at the time. The declaration emerged in the late 18th century out of war and revolution. It encountered opposition as democracy and individual rights were frequently regarded as synonymous with anarchy and subversion. This declaration embodies ideals and aspirations towards which France pledged to struggle in the future.

The text, translated into English, of the Declaration:

The representatives of the French People, formed into a National Assembly, considering ignorance, forgetfulness or contempt of the rights of man to be the only causes of public misfortunes and the corruption of Governments, have resolved to set forth, in a solemn Declaration, the natural, unalienable and sacred rights of man, to the end that this Declaration, constantly present to all members of the body politic, may remind them unceasingly of their rights and their duties; to the end that the acts of the legislative power and those of the executive power, since they may be continually compared with the aim of every political institution, may thereby be the more respected; to the end that the demands of the citizens, founded henceforth on simple and incontestable principles, may always be directed toward the maintenance of the Constitution and the happiness of all.

In consequence whereof, the National Assembly recognizes and declares, in the presence and under the auspices of the Supreme Being, the following Rights of Man and of the Citizen.

- Men are born and remain free and equal in rights. Social distinctions may be based only on considerations of the common good.

- The aim of every political association is the preservation of the natural and imprescriptible rights of Man. These rights are Liberty, Property, Safety and Resistance to Oppression.

- The principle of any Sovereignty lies primarily in the Nation. No corporate body, no individual may exercise any authority that does not expressly emanate from it.

- Liberty consists in being able to do anything that does not harm others: thus, the exercise of the natural rights of every man has no bounds other than those that ensure to the other members of society the enjoyment of these same rights. These bounds may be determined only by Law.

- The Law has the right to forbid only those actions that are injurious to society. Nothing that is not forbidden by Law may be hindered, and no one may be compelled to do what the Law does not ordain.

- The Law is the expression of the general will. All citizens have the right to take part, personally or through their representatives, in its making. It must be the same for all, whether it protects or punishes. All citizens, being equal in its eyes, shall be equally eligible to all high offices, public positions and employments, according to their ability, and without other distinction than that of their virtues and talents.

- No man may be accused, arrested or detained except in the cases determined by the Law, and following the procedure that it has prescribed. Those who solicit, expedite, carry out, or cause to be carried out arbitrary orders must be punished; but any citizen summoned or apprehended by virtue of the Law, must give instant obedience; resistance makes him guilty.

- The Law must prescribe only the punishments that are strictly and evidently necessary; and no one may be punished except by virtue of a Law drawn up and promulgated before the offense is committed, and legally applied.

- As every man is presumed innocent until he has been declared guilty, if it should be considered necessary to arrest him, any undue harshness that is not required to secure his person must be severely curbed by Law.

- No one may be disturbed on account of his opinions, even religious ones, as long as the manifestation of such opinions does not interfere with the established Law and Order.

- The free communication of ideas and of opinions is one of the most precious rights of man. Any citizen may therefore speak, write and publish freely, except what is tantamount to the abuse of this liberty in the cases determined by Law.

- To guarantee the Rights of Man and of the Citizen a public force is necessary; this force is therefore established for the benefit of all, and not for the particular use of those to whom it is entrusted.

- For the maintenance of the public force, and for administrative expenses, a general tax is indispensable; it must be equally distributed among all citizens, in proportion to their ability to pay.

- All citizens have the right to ascertain, by themselves, or through their representatives, the need for a public tax, to consent to it freely, to watch over its use, and to determine its proportion, basis, collection and duration.

- Society has the right to ask a public official for an accounting of his administration.

- Any society in which no provision is made for guaranteeing rights or for the separation of powers, has no Constitution.

- Since the right to Property is inviolable and sacred, no one may be deprived thereof, unless public necessity, legally ascertained, obviously requires it, and just and prior indemnity has been paid

RSS Feed

RSS Feed