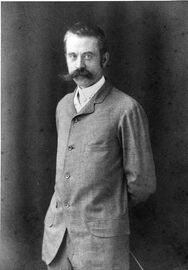

Henry Kendall Shaw

Henry Kendall Shaw Harry Kendall Thaw (February 12, 1871 – February 22, 1947) was the son of coal and railroad baron William Thaw Sr. of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, United States. Heir to a multimillion-dollar fortune, the younger Thaw is most notable for shooting and killing the renowned architect Stanford White on June 25, 1906, on the rooftop of New York City's Madison Square Garden in front of hundreds of witnesses.

Thaw had harbored an obsessive hatred of White, believing he had blocked Thaw's access to the social elite of New York. White had also had a previous relationship with Thaw's wife, the model/chorus girl Evelyn Nesbit, when she was 16–17 years old, which had allegedly begun with White plying Nesbit with alcohol (and possibly drugs) and raping her while she was unconscious. In Thaw's mind, the relationship had "ruined" her. Thaw's trial for murder was heavily publicized in the press, to the extent that it was called the "trial of the century". After one hung jury, he was found not guilty by reason of insanity.

Plagued by mental illness throughout his life that was evident even in his childhood, Thaw spent money lavishly to fund his obsessive partying, drug addiction, abusive behavior toward those around him, and gratification of his sexual appetites. The Thaw family's wealth allowed them to buy the silence of anyone who threatened to make public the worst of Thaw's reckless behavior and licentious transgressions. However, he had several additional serious confrontations with the criminal justice system, one of which resulted in seven years' confinement in a mental institution.

Stanford White

Stanford White All these snubs, Thaw was convinced, were directly or indirectly due to the intervention of the city's social lion, lauded architect Stanford White, who would not countenance Thaw's entry into these exclusive clubs. Thaw's narcissism rebelled at such a state of affairs and ignited a virulent animosity towards White. This was the first identifiable incident in a long line of perceived indignities heaped on Thaw, who maintained the unshakable certainty that his victimization was all orchestrated by White.

A second incident furthered Thaw's paranoid obsession with White. A disgruntled showgirl whom Thaw had publicly insulted reaped revenge when she sabotaged a lavish party Thaw had planned by hijacking all the female invitees and transplanting the festivities to White's infamous Tower room at Madison Square Garden. Thaw, stubbornly ignorant of the real cause of the chain of events, once again blamed White for single-handedly destroying his revelries. Thaw's social humiliation was completed when the episode was reported in the gossip columns. Thaw was left with a stag group of guests, and a glaring absence of "doe-eyed girlies".

Evelyn Nesbit Thaw

Evelyn Nesbit Thaw On June 25, 1906, Thaw and Nesbit were stopping in New York briefly before boarding a luxury liner bound for a European holiday. Thaw had purchased tickets for himself, two of his male friends, and his wife for a new show, Mam'zelle Champagne, playing on the rooftop theatre of Madison Square Garden. In spite of the suffocating heat, which did not abate as night fell, Thaw inappropriately wore over his tuxedo a long black overcoat, which he refused to take off throughout the entire evening.

At 11:00 p.m., as the stage show was coming to a close, White appeared, taking his place at the table that was customarily reserved for him. Thaw had been agitated all evening, and abruptly bounced back and forth from his own table throughout the performance. Spotting White's arrival, Thaw tentatively approached him several times, each time withdrawing in hesitation. During the finale, "I Could Love A Million Girls", Thaw produced a pistol, and standing some two feet from his target, fired three shots at White, killing him instantly. Part of White's blood-covered face was torn away and the rest of his features were unrecognizable, blackened by gunpowder. Thaw remained standing over White's fallen body, displaying the gun aloft in the air, resoundingly proclaiming, according to witness reports, "I did it because he ruined my wife! He had it coming to him! He took advantage of the girl and then abandoned her!"(The key witness allowed that he wasn't completely sure he heard Thaw correctly – that he might have said "he ruined my life" rather than "he ruined my wife".)

The crowd initially suspected the shooting might be part of the show, as elaborate practical jokes were popular in high society at the time. Soon, however, it became apparent that White was dead. Thaw, still brandishing the gun high above his head, walked through the crowd and met Nesbit at the elevator. When she asked what he had done, Thaw purportedly replied, "It's all right, I probably saved your life."

Thaw was charged with first-degree murder and denied bail. A newspaper photo shows Thaw in The Tombs prison seated at a formal table setting, dining on a meal catered for him by Delmonico's restaurant. In the background is further evidence of the preferential treatment provided to him. Conspicuously absent is the standard issue jail cell cot; during his confinement Thaw slept in a brass bed. Exempted from wearing prisoner's garb, he was allowed to wear his own custom tailored clothes. The jail's doctor was induced to allow Thaw a daily ration of champagne and wine. In his jail cell, in the days following his arrest, it was reported that Thaw heard the heavenly voices of young girls calling to him, which he interpreted as a sign of divine approval. He was in a euphoric mood; Thaw was unshakable in his belief that the public would applaud the man who had rid the world of the menace of Stanford White.

As early as the morning following the shooting, news coverage became both chaotic and single-minded, and ground forward with unrelenting momentum. Any person, place or event, no matter how peripheral to the incident, was seized on by reporters and hyped as newsworthy copy. Facts were thin but sensationalist reportage was plentiful in this, the heyday of yellow journalism. The hard-boiled news reporters were bolstered by a contingent of counterparts, christened "Sob Sisters", whose stock-in-trade was the human interest piece, heavy on sentimental tropes and melodrama, crafted to pull on the emotions and punch them up to fever pitch. The rampant interest in the White murder and its key players were used by both the defense and prosecution to feed malleable reporters any "scoops" that would give their respective sides an advantage in the public forum. Thaw's mother, as was her custom, primed her own publicity machine through monetary pay-offs. The district attorney's office took on the services of a Pittsburgh public relations firm, McChesney and Carson, backing a print smear campaign aimed at discrediting Thaw and Nesbit. Pittsburgh newspapers displayed lurid headlines, a sample of which blared, "Woman Whose Beauty Spelled Death and Ruin". Only one week after the shooting, a nickelodeon film, Rooftop Murder, was released, rushed into production by Thomas Edison.

The main issue in the case was the question of premeditation. At the outset, the formidable District Attorney, William Travers Jerome, preferred not to take the case to trial by having Thaw declared legally insane. This was to serve a two-fold purpose. The approach would save time and money, and of equal if not greater consideration, it would avoid the unfavorable publicity that would no doubt be generated from disclosures made during testimony on the witness stand—revelations that threatened to discredit many of high social standing. Thaw's first defense attorney, Lewis Delafield, concurred with the prosecutorial position, seeing that an insanity plea was the only way to avoid a death sentence for their client. Thaw dismissed Delafield, who he was convinced wanted to "railroad [him] to Matteawan as the half-crazy tool of a dissolute woman".

Thaw's mother, however, was adamant that her son not be stigmatized by clinical insanity. She pressed for the defense to follow a compromise strategy; one of temporary insanity, or what in that era was referred to as a "brainstorm". Acutely conscious of the insanity in her side of the family, and after years of protecting her son's hidden life, she feared her son's past would be dragged out into the open, ripe for public scrutiny. Protecting the Thaw family reputation had become nothing less than a vigilant crusade for Thaw's mother. She proceeded to hire a team of doctors, at a cost of half a million dollars, to substantiate that her son's act of murder constituted a single aberrant act.

Possibly concocted by the yellow press in concert with Thaw's attorneys, the temporary insanity defense, in Thaw's case, was dramatized as a uniquely American phenomenon. Branded "dementia Americana", this catch phrase encompassed the male prerogative to revenge any woman whose sacred chastity had been violated. In essence, murder motivated by such a circumstance was the act of a man justifiably unbalanced.

Thaw was tried twice for the murder of White. Due to the unusual amount of publicity the case had received, it was ordered that the jury members be sequestered—the first time in the history of American jurisprudence that such a restriction was ordered. The trial proceedings began on January 23, 1907, and the jury went into deliberation on April 11. After forty-seven hours, the twelve jurors emerged deadlocked. Seven had voted guilty, and five voted not guilty. Thaw was outraged that the trial had not vindicated the murder, that the jurors had not recognized it as the act of a chivalrous man defending innocent womanhood. He went into fits of physical flailing and crying when he considered the very real possibility that he would be labeled a madman and imprisoned in an asylum. The second trial took place from January 1908 through February 1, 1908.

At the second trial, Thaw pleaded temporary insanity. This legal strategy was developed by Thaw's new chief defense counsel, Martin W. Littleton, whom Thaw and his mother had retained for $25,000 (equivalent to $720,000 in 2020). Thaw was found not guilty by reason of insanity, and sentenced to incarceration for life at the Matteawan State Hospital for the Criminally Insane in Fishkill, New York. His wealth allowed him to arrange accommodations for his comfort and be granted privileges not given to the general Matteawan population.

Nesbit had testified at both trials. It is conjectured that the Thaws promised her a comfortable financial future if she provided testimony at trial favorable to Thaw's case. It was a conditional agreement; if the outcome proved negative, she would receive nothing. The rumored amount of money the Thaws pledged for her cooperation ranged from $25,000 to $1 million. Throughout the prolonged court proceedings, Nesbit had received inconsistent financial support from the Thaws, made to her through their attorneys. After the close of the second trial, the Thaws virtually abandoned Nesbit, cutting off all funds. However, in an interview Nesbit's grandson, Russell Thaw, gave to the Los Angeles Times in 2005, it was his belief that Nesbit received $25,000 from the family after the end of the second trial. Nesbit and Thaw divorced in 1915.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed