Joan was the daughter of Jacques d'Arc and Isabelle Romée, living in Domrémy, a village which was then in the French part of the Duchy of Bar. Joan's parents owned about 50 acres (20 hectares) of land and her father supplemented his farming work with a minor position as a village official, collecting taxes and heading the local watch. They lived in an isolated patch of eastern France that remained loyal to the French crown despite being surrounded by pro-Burgundian lands. Several local raids occurred during her childhood and on one occasion her village was burned. Joan was illiterate and it is believed that her letters were dictated by her to scribes and she signed her letters with the help of others.

At her trial, Joan stated that she was about 19 years old, which implies she thought she was born around 1412. She later testified that she experienced her first vision in 1425 at the age of 13, when she was in her "father's garden" and saw visions of figures she identified as Saint Michael, Saint Catherine, and Saint Margaret, who told her to drive out the English and take the Dauphin to Reims for his consecration. She said she cried when they left, as they were so beautiful.

At the age of 16, she asked a relative named Durand Lassois to take her to the nearby town of Vaucouleurs, where she petitioned the garrison commander, Robert de Baudricourt, for an armed escort to take her to the French Royal Court at Chinon. Baudricourt's sarcastic response did not deter her. She returned the following January and gained support from two of Baudricourt's soldiers: Jean de Metz and Bertrand de Poulengy. According to Jean de Metz, she told him that "I must be at the King's side ... there will be no help (for the kingdom) if not from me. Although I would rather have remained spinning [wool] at my mother's side ... yet must I go and must I do this thing, for my Lord wills that I do so." Under the auspices of Jean de Metz and Bertrand de Poulengy, she was given a second meeting, where she made a prediction about a military reversal at the Battle of Rouvray near Orléans several days before messengers arrived to report it. According to the Journal du Siége d'Orléans, which portrays Joan as a miraculous figure, Joan came to know of the battle through "Divine grace" while tending her flocks in Lorraine and used this divine revelation to persuade Baudricourt to take her to the Dauphin.

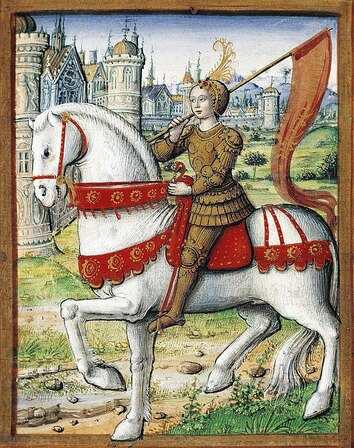

Robert de Baudricourt granted Joan an escort to visit Chinon after news from Orleans confirmed her assertion of the defeat. She made the journey through hostile Burgundian territory disguised as a male soldier, a fact that would later lead to charges of "cross-dressing" against her, although her escort viewed it as a normal precaution. Two of the members of her escort said they and the people of Vaucouleurs provided her with this clothing, and had suggested it to her.

Joan's first meeting with Charles took place at the Royal Court in the town of Chinon in 1429, when she was aged 17 and he 26. After arriving at the Court she made a strong impression on Charles during a private conference with him. During this time Charles' mother-in-law Yolande of Aragon was planning to finance a relief expedition to Orléans. Joan asked for permission to travel with the army and wear protective armor, which was provided by the Royal government. She depended on donated items for her armor, horse, sword, banner, and other items utilized by her entourage. Historian Stephen W. Richey explains her attraction to the royal court by pointing out that they may have viewed her as the only source of hope for a regime that was near collapse:

After years of one humiliating defeat after another, both the military and civil leadership of France were demoralized and discredited. When the Dauphin Charles granted Joan's urgent request to be equipped for war and placed at the head of his army, his decision must have been based in large part on the knowledge that every orthodox, every rational option had been tried and had failed. Only a regime in the final straits of desperation would pay any heed to an illiterate farm girl who said that the voice of God was instructing her to take charge of her country's army and lead it to victory

Upon her arrival on the scene, Joan effectively turned the longstanding Anglo-French conflict into a religious war,a course of action that was not without risk. Charles' advisers were worried that unless Joan's orthodoxy could be established beyond doubt—that she was not a heretic or a sorceress—Charles' enemies could easily make the allegation that his crown was a gift from the devil. To circumvent this possibility, the Dauphin ordered background inquiries and a theological examination at Poitiers to verify her morality. In April 1429, the commission of inquiry "declared her to be of irreproachable life, a good Christian, possessed of the virtues of humility, honesty and simplicity." The theologians at Poitiers did not render a decision on the issue of divine inspiration; rather, they informed the Dauphin that there was a "favorable presumption" to be made on the divine nature of her mission. This convinced Charles, but they also stated that he had an obligation to put Joan to the test. "To doubt or abandon her without suspicion of evil would be to repudiate the Holy Spirit and to become unworthy of God's aid", they declared. They recommended that her claims should be put to the test by seeing if she could lift the siege of Orléans as she had predicted.

She arrived at the besieged city of Orléans on 29 April 1429. Jean d'Orléans, the acting head of the ducal family of Orléans on behalf of his captive half-brother, initially excluded her from war councils and failed to inform her when the army engaged the enemy. However, his decision to exclude her did not prevent her presence at most councils and battles. The extent of her actual military participation and leadership is a subject of debate among historians. On the one hand, Joan stated that she carried her banner in battle and had never killed anyone, preferring her banner "forty times" better than a sword; and the army was always directly commanded by a nobleman, such as the Duke of Alençon for example. On the other hand, many of these same noblemen stated that Joan had a profound effect on their decisions since they often accepted the advice she gave them, believing her advice was divinely inspired. In either case, historians agree that the army enjoyed remarkable success during her brief time with it.

A truce with England during the following few months left Joan with little to do. On 23 March 1430, she dictated a threatening letter to the Hussites, a dissident group which had broken with the Roman Catholic Church on a number of doctrinal points and had defeated several previous crusades sent against them. Joan's letter promises to "remove your madness and foul superstition, taking away either your heresy or your lives." Joan, an ardent Catholic who hated all forms of heresy, also sent a letter challenging the English to leave France and go with her to Bohemia to fight the Hussites, an offer that went unanswered.

The truce with England quickly came to an end. Joan traveled to Compiègne the following May to help defend the city against an English and Burgundian siege. On 23 May 1430 she was with a force that attempted to attack the Burgundian camp at Margny north of Compiègne, but was ambushed and captured. When the troops began to withdraw toward the nearby fortifications of Compiègne after the advance of an additional force of 6,000 Burgundians, Joan stayed with the rear guard. Burgundian troops surrounded the rear guard, and she was pulled off her horse by an archer. She agreed to surrender to a pro-Burgundian nobleman named Lionel of Wandomme, a member of Jean de Luxembourg's unit.

Joan was imprisoned by the Burgundians at Beaurevoir Castle. She made several escape attempts, on one occasion jumping from her 70-foot (21 m) tower, landing on the soft earth of a dry moat, after which she was moved to the Burgundian town of Arras. The English negotiated with their Burgundian allies to transfer her to their custody, with Bishop Pierre Cauchon of Beauvais, an English partisan, assuming a prominent role in these negotiations and her later trial.[better source needed] The final agreement called for the English to pay the sum of 10,000 livres tournoisto obtain her from Jean de Luxembourg, a member of the Council of Duke Philip of Burgundy.

The English moved Joan to the city of Rouen, which served as their main headquarters in France. The Armagnacs attempted to rescue her several times by launching military campaigns toward Rouen while she was held there. One campaign occurred during the winter of 1430–1431, another in March 1431, and one in late May shortly before her execution. These attempts were beaten back. Charles VII threatened to "exact vengeance" upon Burgundian troops whom his forces had captured and upon "the English and women of England" in retaliation for their treatment of Joan.

The trial for heresy was politically motivated. The tribunal was composed entirely of pro-English and Burgundian clerics, and overseen by English commanders including the Duke of Bedford and the Earl of Warwick. In the words of the British medievalist Beverly Boyd, the trial was meant by the English Crown to be "a ploy to get rid of a bizarre prisoner of war with maximum embarrassment to their enemies". Legal proceedings commenced on 9 January 1431 at Rouen, the seat of the English occupation government. The procedure was suspect on a number of points, which would later provoke criticism of the tribunal by the chief inquisitor who investigated the trial after the war.

Under ecclesiastical law, Bishop Cauchon lacked jurisdiction over the case. Cauchon owed his appointment to his partisan support of the English Crown, which financed the trial. The low standard of evidence used in the trial also violated inquisitorial rules. Clerical notary Nicolas Bailly, who was commissioned to collect testimony against Joan, could find no adverse evidence. Without such evidence the court lacked grounds to initiate a trial. Opening a trial anyway, the court also violated ecclesiastical law by denying Joan the right to a legal adviser. In addition, stacking the tribunal entirely with pro-English clergy violated the medieval Church's requirement that heresy trials be judged by an impartial or balanced group of clerics. Upon the opening of the first public examination, Joan complained that those present were all partisans against her and asked for "ecclesiastics of the French side" to be invited in order to provide balance. This request was denied.

The Vice-Inquisitor of Northern France (Jean Lemaitre) objected to the trial at its outset, and several eyewitnesses later said he was forced to cooperate after the English threatened his life. Some of the other clergy at the trial were also threatened when they refused to cooperate, including a Dominican friar named Isambart de la Pierre. These threats, and the domination of the trial by a secular government, were violations of the Church's rules and undermined the right of the Church to conduct heresy trials without secular interference.

The trial record contains statements from Joan that the eyewitnesses later said astonished the court, since she was an illiterate peasant and yet was able to evade the theological pitfalls the tribunal had set up to entrap her. The transcript's most famous exchange is an exercise in subtlety: "Asked if she knew she was in God's grace, she answered, 'If I am not, may God put me there; and if I am, may God so keep me. I should be the saddest creature in the world if I knew I were not in His grace.'" The question is a scholarly trap. Church doctrine held that no one could be certain of being in God's grace. If she had answered yes, then she would have been charged with heresy. If she had answered no, then she would have confessed her own guilt. The court notary Boisguillaume later testified that at the moment the court heard her reply, "Those who were interrogating her were stupefied."

Several members of the tribunal later testified that important portions of the transcript were falsified by being altered in her disfavor. Under Inquisitorial guidelines, Joan should have been confined in an ecclesiastical prison under the supervision of female guards (i.e., nuns). Instead, the English kept her in a secular prison guarded by their own soldiers. Bishop Cauchon denied Joan's appeals to the Council of Basel and the Pope, which should have stopped his proceeding.

The twelve articles of accusation which summarized the court's findings contradicted the court record, which had already been doctored by the judges. Under threat of immediate execution, the illiterate defendant signed an abjuration document that she did not understand. The court substituted a different abjuration in the official record.

Heresy was a capital crime only for a repeat offense; therefore, a repeat offense of "cross-dressing" was now arranged by the court, according to the eyewitnesses. Joan agreed to wear feminine clothing when she abjured, which created a problem. According to the later descriptions of some of the tribunal members, she had previously been wearing soldiers' clothing in prison. Since wearing men's hosen enabled her to fasten her hosen, boots and doublet together, this deterred rape by making it difficult for her guards to pull her clothing off. She was evidently afraid to give up this clothing even temporarily because it was likely to be confiscated by the judge and she would thereby be left without protection. A woman's dress offered no such protection. A few days after her abjuration, when she was forced to wear a dress, she told a tribunal member that "a great English lord had entered her prison and tried to take her by force." She resumed male attire either as a defense against molestation or, in the testimony of Jean Massieu, because her dress had been taken by the guards and she was left with nothing else to wear.

Her resumption of male military clothing was labeled a relapse into heresy for cross-dressing, although this would later be disputed by the inquisitor who presided over the appeals court that examined the case after the war. Medieval Catholic doctrine held that cross-dressing should be evaluated based on context, as stated in the Summa Theologica by St. Thomas Aquinas, which says that necessity would be a permissible reason for cross-dressing. This would include the use of clothing as protection against rape if the clothing would offer protection. In terms of doctrine, she had been justified in disguising herself as a pageboy during her journey through enemy territory, and she was justified in wearing armor during battle and protective clothing in camp and then in prison. The Chronique de la Pucelle states that it deterred molestation while she was camped in the field. When her soldiers' clothing was not needed while on campaign, she was said to have gone back to wearing a dress. Clergy who later testified at the posthumous appellate trial affirmed that she continued to wear male clothing in prison to deter molestation and rape.

Joan referred the court to the Poitiers inquiry when questioned on the matter. The Poitiers record no longer survives, but circumstances indicate the Poitiers clerics had approved her practice. She also kept her hair cut short through her military campaigns and while in prison. Her supporters, such as the theologian Jean Gerson, defended her hairstyle for practical reasons, as did Inquisitor Brehal later during the appellate trial. Nonetheless, at the trial in 1431 she was condemned and sentenced to die. Boyd described Joan's trial as so "unfair" that the trial transcripts were later used as evidence for canonizing her in the 20th century.

The posthumous retrial opened after the war ended. Pope Callixtus III authorized this proceeding, also known as the "nullification trial", at the request of Inquisitor-General Jean Bréhal and Joan's mother Isabelle Romée. The purpose of the trial was to investigate whether the trial of condemnation and its verdict had been handled justly and according to canon law. Investigations started with an inquest by Guillaume Bouillé, a theologian and former rector of the University of Paris (Sorbonne).

Bréhal conducted an investigation in 1452. A formal appeal followed in November 1455. The appellate process involved clergy from throughout Europe and observed standard court procedure. A panel of theologians analyzed testimony from 115 witnesses. Bréhal drew up his final summary in June 1456, which describes Joan as a martyr and implicated the late Pierre Cauchon with heresy for having convicted an innocent woman in pursuit of a secular vendetta. The technical reason for her execution had been a Biblical clothing law. The nullification trial reversed the conviction in part because the condemnation proceeding had failed to consider the doctrinal exceptions to that stricture. The appellate court declared her innocent on 7 July 1456.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed