Philadelphia's city bell had been used to alert the public to proclamations or civic danger since the city's 1682 founding. The original bell hung from a tree behind the Pennsylvania State House (now known as Independence Hall) and was said to have been brought to the city by its founder, William Penn. In 1751, with a bell tower being built in the Pennsylvania State House, civic authorities sought a bell of better quality that could be heard at a greater distance in the rapidly expanding city. Isaac Norris, speaker of the Pennsylvania Provincial Assembly, gave orders to the colony's London agent, Robert Charles, to obtain a "good Bell of about two thousands pound weight".

The bell was to contain an inscription quoting Leviticus ch. 24 v. 10, "Proclaim LIBERTY Throughout all the Land unto all the Inhabitants Thereof." Thus began one of the first great myths of the bell, which was that it's inscription was an early statement of colonial desire for independence from England. However, there is no evidence as to why this particular verse was chosen and at the time there was very little sentiment for independence. Rather, the prevailing view was that the colonies should be afford equality with, rather than independence from, Great Britain.

Upon its arrival in Philadelphia, the bell was mounted on a stand to test the sound, and at the first strike of the clapper, the bell's rim cracked. Philadelphia authorities tried to return it by ship, but the master of the vessel that had brought it was unable (or refused) to take it on board. Thus it had to be recast by a local foundrymen, Pass and Stow. Though they were inexperienced in bell casting, Pass had headed the Mount Holly Iron Foundry in neighboring New Jersey and came from Malta that had a tradition of bell casting. Stow, on the other hand, was only four years out of his apprenticeship as a brass founder. At Stow's foundry on Second Street, the bell was broken into small pieces, melted down, and cast into a new bell. The two founders decided that the metal was too brittle, and augmented the bell metal by about ten percent, using copper. The bell was ready in March 1753, and Norris reported that the lettering (that included the founders' names and the year) was even clearer on the new bell than on the old.

This we come to the second myth, or perhaps we should say controversy, over the bell. Because the bell was broken into pieces and entirely recast with additional ore, was it in fact the same bell or a new bell? The question is more important than a mere sophistry would suggest, because the "English" or "American" nature of the bell became a political tool for, among others, former President Benjamin Harrison, who, speaking as the bell passed through Indianapolis, stated, "This old bell was made in England, but it had to be re-cast in America before it was attuned to proclaim the right of self-government and the equal rights of men." Accordingly the first (yes, first) recasting of the bell became symbolic well after the fact, with some even claiming that the bell had been deliberately made with poor quality ore to make the bell's proclamation of Liberty to "ring hollow" and it's recasting was a message to the old country that Americans could take what was English and make it better. The truth is more likely that the bell's original casters were cutting corners and used inferior ore to reduce expenses.

City officials scheduled a public celebration with free food and drink for the testing of the recast bell. When the bell was struck, it did not break, but the sound produced was described by one hearer as like two coal scuttles being banged together. Mocked by the crowd, Pass and Stow hastily took the bell away and again recast it. When the fruit of the two founders' renewed efforts was brought forth in June 1753, the sound was deemed satisfactory, though Norris indicated that he did not personally like it. The bell was hung in the steeple of the State House the same month.

Dissatisfied with the bell, Norris instructed Charles to order a second one, and see if Lester and Pack would take back the first bell and credit the value of the metal towards the bill. In 1754, the Assembly decided to keep both bells; the new one was attached to the tower clock while the old bell was, by vote of the Assembly, devoted "to such Uses as this House may hereafter appoint." The Pass and Stow bell was used to summon the Assembly.[19] One of the earliest documented mentions of the bell's use is in a letter from Benjamin Franklin to Catherine Ray dated October 16, 1755: "Adieu. The Bell rings, and I must go among the Grave ones, and talk Politiks." The bell was rung in 1760 to mark the accession of George III to the throne. In the early 1760s, the Assembly allowed a local church to use the State House for services and the bell to summon worshipers, while the church's building was being constructed.[20] The bell was also used to summon people to public meetings, and in 1772, a group of citizens complained to the Assembly that the bell was being rung too frequently.

Despite the legends that have grown up about the Liberty Bell, it did not ring on July 4, 1776 (at least not for any reason connected with independence), as no public announcement was made of the Declaration of Independence. When the Declaration was publicly read on July 8, 1776, there was a ringing of bells, and while there is no contemporary account of this particular bell ringing, most authorities agree that the Liberty Bell was among the bells that rang. However, there is some chance that the poor condition of the State House bell tower prevented the bell from ringing.

After Washington's defeat at the Battle of Brandywine on September 11, 1777, the revolutionary capital of Philadelphia was defenseless, and the city prepared for what was seen as an inevitable British attack. Bells could easily be recast into munitions, and locals feared the Liberty Bell and other bells would meet this fate. The bell was hastily taken down from the tower, and sent by heavily guarded wagon train to the town of Bethlehem. Local wagoneers transported the bell to the Zion German Reformed Church in Northampton Town, now Allentown, where it waited out the British occupation of Philadelphia under the church floor boards. It was returned to Philadelphia in June 1778, after the British departure. With the steeple of the State House in poor condition (the steeple was subsequently torn down and later restored), the bell was placed in storage, and it was not until 1785 that it was again mounted for ringing.

Placed on an upper floor of the State House, the bell was rung in the early years of independence on the Fourth of July and on Washington's Birthday, as well as on Election Day to remind voters to hand in their ballots. It also rang to call students at the University of Pennsylvania to their classes at nearby Philosophical Hall. Until 1799, when the state capital was moved to Lancaster, it again rang to summon legislators into session. When Pennsylvania, having no further use for its State House, proposed to tear it down and sell the land for building lots, the City of Philadelphia purchased the land, together with the building, including the bell, for $70,000, equal to $1,067,431 today. In 1828, the city sold the second Lester and Pack bell to St. Augustine's Roman Catholic Church that was burned down by an anti-Catholic mob in the Philadelphia Nativist Riots of 1844. The remains of the bell were recast; the new bell is now located at Villanova University.

It is uncertain how the bell came to be cracked; the damage occurred sometime between 1817 and 1846. The bell is mentioned in a number of newspaper articles during that time; no mention of a crack can be found until 1846. In fact, in 1837, the bell was depicted in an anti-slavery publication—uncracked. In February 1846 Public Ledger reported that the bell had been rung on February 23, 1846, in celebration of Washington's Birthday (as February 22 fell on a Sunday, the celebration occurred the next day), and also reported that the bell had long been cracked, but had been "put in order" by having the sides of the crack filed. The paper reported that around noon, it was discovered that the ringing had caused the crack to be greatly extended, and that "the old Independence Bell ... now hangs in the great city steeple irreparably cracked and forever dumb".

The most common story about the cracking of the bell is that it happened when the bell was rung upon the 1835 death of the Chief Justice of the United States, John Marshall. This story originated in 1876, when the volunteer curator of Independence Hall, Colonel Frank Etting, announced that he had ascertained the truth of the story. While there is little evidence to support this view, it has been widely accepted and taught. Other claims regarding the crack in the bell include stories that it was damaged while welcoming Lafayette on his return to the United States in 1824, that it cracked announcing the passing of the British Catholic Relief Act 1829, and that some boys had been invited to ring the bell, and inadvertently damaged it. David Kimball, in his book compiled for the National Park Service, suggests that it most likely cracked sometime between 1841 and 1845, either on the Fourth of July or on Washington's Birthday.

The Pass and Stow bell was first termed "the Liberty Bell" in the New York Anti-Slavery Society's journal, Anti-Slavery Record. In an 1835 piece, "The Liberty Bell", Philadelphians were castigated for not doing more for the abolitionist cause. Two years later, in another work of that society, the journal Liberty featured an image of the bell as its frontispiece, with the words "Proclaim Liberty". In 1839, Boston's Friends of Liberty, another abolitionist group, titled their journal The Liberty Bell. The same year, William Lloyd Garrison's anti-slavery publication The Liberator reprinted a Boston abolitionist pamphlet containing a poem entitled "The Liberty Bell" that noted that, at that time, despite its inscription, the bell did not proclaim liberty to all the inhabitants of the land.

A great part of the modern image of the bell as a relic of the proclamation of American independence was forged by writer George Lippard. On January 2, 1847, his story "Fourth of July, 1776" appeared in the Saturday Courier. The short story depicted an aged bellman on July 4, 1776, sitting morosely by the bell, fearing that Congress would not have the courage to declare independence. At the most dramatic moment, a young boy appears with instructions for the old man: to ring the bell. It was subsequently published in Lippard's collected stories. The story was widely reprinted and closely linked the Liberty Bell to the Declaration of Independence in the public mind. The elements of the story were reprinted in early historian Benson J. Lossing's The Pictorial Field Guide to the Revolution (published in 1850) as historical fact,[38] and the tale was widely repeated for generations after in school primers.

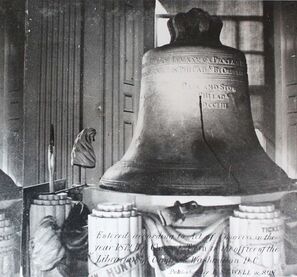

In 1848, with the rise of interest in the bell, the city decided to move it to the Assembly Room (also known as the Declaration Chamber) on the first floor, where the Declaration and United States Constitution had been debated and signed. The city constructed an ornate pedestal for the bell. The Liberty Bell was displayed on that pedestal for the next quarter-century, surmounted by an eagle (originally sculpted, later stuffed). In 1853, President Franklin Pierce visited Philadelphia and the bell, and spoke of the bell as symbolizing the American Revolution and American liberty. At the time, Independence Hall was also used as a courthouse, and African-American newspapers pointed out the incongruity of housing a symbol of liberty in the same building in which federal judges were holding hearings under the Fugitive Slave Act.

In February 1861, the President-elect, Abraham Lincoln, came to the Assembly Room and delivered an address en route to his inauguration in Washington DC. In 1865, Lincoln's body was returned to the Assembly Room after his assassination for a public viewing of his body, en route to his burial in Springfield, Illinois. Due to time constraints, only a small fraction of those wishing to pass by the coffin were able to; the lines to see the coffin were never less than 3 miles (4.8 km) long. Nevertheless, between 120,000 and 140,000 people were able to pass by the open casket and then the bell, carefully placed at Lincoln's head so mourners could read the inscription, "Proclaim Liberty throughout all the land unto all the inhabitants thereof."

In 1876, city officials discussed what role the bell should play in the nation's Centennial festivities. Some wanted to repair it so it could sound at the Centennial Exposition being held in Philadelphia, but the idea was not adopted; the bell's custodians concluded that it was unlikely that the metal could be made into a bell that would have a pleasant sound, and that the crack had become part of the bell's character. Instead, a replica weighing 13,000 pounds (5,900 kg) (1,000 pounds for each of the original states) was cast. The metal used for what was dubbed "the Centennial Bell" included four melted-down cannons: one used by each side in the American Revolutionary War, and one used by each side in the Civil War. That bell was sounded at the Exposition grounds on July 4, 1876, was later recast to improve the sound, and today is the bell attached to the clock in the steeple of Independence Hall. While the Liberty Bell did not go to the Exposition, a great many Exposition visitors came to visit it, and its image was ubiquitous at the Exposition grounds—myriad souvenirs were sold bearing its image or shape, and state pavilions contained replicas of the bell made of substances ranging from stone to tobacco. In 1877, the bell was hung from the ceiling of the Assembly Room by a chain with thirteen links.

Between 1885 and 1915, the Liberty Bell made seven trips to various expositions and celebrations. Each time, the bell traveled by rail, making a large number of stops along the way so that local people could view it. By 1885, the Liberty Bell was widely recognized as a symbol of freedom, and as a treasured relic of Independence, and was growing still more famous as versions of Lippard's legend were reprinted in history and school books. In early 1885, the city agreed to let it travel to New Orleans for the World Cotton Centennial exposition. Large crowds mobbed the bell at each stop. In Biloxi, Mississippi, the former President of the Confederate States of America, Jefferson Davis came to the bell. Davis delivered a speech paying homage to it, and urging national unity.[51] In 1893, it was sent to Chicago's World Columbian Exposition to be the centerpiece of the state's exhibit in the Pennsylvania Building. On July 4, 1893, in Chicago, the bell was serenaded with the first performance of The Liberty Bell March, conducted by "America's Bandleader", John Philip Sousa. Philadelphians began to cool to the idea of sending it to other cities when it returned from Chicago bearing a new crack, and each new proposed journey met with increasing opposition. It was also found that the bell's private watchman had been cutting off small pieces for souvenirs. The city placed the bell in a glass-fronted oak case. In 1898, it was taken out of the glass case and hung from its yoke again in the tower hall of Independence Hall, a room that would remain its home until the end of 1975. A guard was posted to discourage souvenir hunters who might otherwise chip at it.

By 1909, the bell had made six trips, and not only had the cracking become worse, but souvenir hunters had deprived it of over one percent of its weight. (Its weight was reported as 2,080 lb (940 kg) in 1904. When, in 1912, the organizers of the Panama-Pacific International Exposition requested the bell for the 1915 fair in San Francisco, the city was reluctant to let it travel again. The city finally decided to let it go as the bell had never been west of St. Louis, and it was a chance to bring it to millions who might never see it otherwise. However, in 1914, fearing that the cracks might lengthen during the long train ride, the city installed a metal support structure inside the bell, generally called the "spider." In February 1915, the bell was tapped gently with wooden mallets to produce sounds that were transmitted to the fair as the signal to open it, a transmission that also inaugurated transcontinental telephone service. Some five million Americans saw the bell on its train journey west. It is estimated that nearly two million kissed it at the fair, with an uncounted number viewing it. The bell was taken on a different route on its way home; again, five million saw it on the return journey. Since the bell returned to Philadelphia, it has been moved out of doors only five times: three times for patriotic observances during and after World War I, and twice as the bell occupied new homes in 1976 and 2003. Chicago and San Francisco had obtained its presence after presenting petitions signed by hundreds of thousands of children. Chicago tried again, with a petition signed by 3.4 million schoolchildren, for the 1933 Century of Progress Exhibition and New York presented a petition to secure a visit from the bell for the 1939 New York World's Fair. Both efforts failed.

In 1924, one of Independence Hall's exterior doors was replaced by glass, allowing some view of the bell even when the building was closed. When Congress enacted the nation's first peacetime draft in 1940, the first Philadelphians required to serve took their oaths of enlistment before the Liberty Bell. Once the war started, the bell was again a symbol, used to sell war bonds. In the early days of World War II, it was feared that the bell might be in danger from saboteurs or enemy bombing, and city officials considered moving the bell to Fort Knox, to be stored with the nation's gold reserves. The idea provoked a storm of protest from around the nation, and was abandoned. Officials then considered building an underground steel vault above which it would be displayed, and into which it could be lowered if necessary. The project was dropped when studies found that the digging might undermine the foundations of Independence Hall. On December 17, 1944, the Whitechapel Bell Foundry offered to recast the bell at no cost as a gesture of Anglo-American friendship. The bell was again tapped on D-Day, as well as in victory on V-E Day and V-J Day.

After World War II, and following considerable controversy, the City of Philadelphia agreed that it would transfer custody of the bell and Independence Hall, while retaining ownership, to the federal government. The city would also transfer various colonial-era buildings it owned. Congress agreed to the transfer in 1948, and three years later Independence National Historical Park was founded, incorporating those properties and administered by the National Park Service (NPS or Park Service).[70] The Park Service would be responsible for maintaining and displaying the bell.[71] The NPS would also administer the three blocks just north of Independence Hall that had been condemned by the state, razed, and developed into a park, Independence Mall.[70]

In the postwar period, the bell became a symbol of freedom used in the Cold War. The bell was chosen for the symbol of a savings bond campaign in 1950. The purpose of this campaign, as Vice President Alben Barkley put it, was to make the country "so strong that no one can impose ruthless, godless ideologies on us". In 1955, former residents of nations behind the Iron Curtain were allowed to tap the bell as a symbol of hope and encouragement to their compatriots. Foreign dignitaries, such as Israeli Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion and West Berlin Mayor Ernst Reuter were brought to the bell, and they commented that the bell symbolized the link between the United States and their nations. During the 1960s, the bell was the site of several protests, both for the civil rights movement, and by various protesters supporting or opposing the Vietnam War.

Almost from the start of its stewardship, the Park Service sought to move the bell from Independence Hall to a structure where it would be easier to care for the bell and accommodate visitors. The first such proposal was withdrawn in 1958, after considerable public protest. The Park Service tried again as part of the planning for the 1976 United States Bicentennial. The Independence National Historical Park Advisory Committee proposed in 1969 that the bell be moved out of Independence Hall, as the building could not accommodate the millions expected to visit Philadelphia for the Bicentennial. In 1972, the Park Service announced plans to build a large glass tower for the bell at the new visitors center at South Third Street and Chestnut Street, two blocks east of Independence Hall, at a cost of $5 million, but citizens again protested the move. Instead, in 1973, the Park Service proposed to build a smaller glass pavilion for the bell at the north end of Independence Mall, between Arch and Race Streets. Philadelphia Mayor Frank Rizzo agreed with the pavilion idea, but proposed that the pavilion be built across Chestnut Street from Independence Hall, which the state feared would destroy the view of the historic building from the mall area. Rizzo's view prevailed, and the bell was moved to a glass-and-steel Liberty Bell Pavilion, about 200 yards (180 m) from its old home at Independence Hall, as the Bicentennial year began.

During the Bicentennial, members of the Procrastinators' Club of America jokingly picketed the Whitechapel Bell Foundry with signs "We got a lemon" and "What about the warranty?" The foundry told the protesters that it would be glad to replace the bell—so long as it was returned in the original packaging. In 1958, the foundry (then trading under the name Mears and Stainbank Foundry) had offered to recast the bell, and was told by the Park Service that neither it nor the public wanted the crack removed. The foundry was called upon, in 1976, to cast a full-size replica of the Liberty Bell (known as the Bicentennial Bell) that was presented to the United States by the British monarch, Queen Elizabeth II, and was housed in the tower once intended for the Liberty Bell, at the former visitor center on South Third Street.

Today, the Liberty Bell weighs 2,080 pounds (940 kg). Its metal is 70% copper and 25% tin, with the remainder consisting of lead, zinc, arsenic, gold and silver. It hangs from what is believed to be its original yoke, made from American elm. While the crack in the bell appears to end at the abbreviation "Philada" in the last line of the inscription, that is merely the 19th century widened crack that was filed out in the hopes of allowing the bell to continue to ring; a hairline crack, extending through the bell to the inside continues generally right and gradually moving to the top of the bell, through the word "and" in "Pass and Stow," then through the word "the" before the word "Assembly" in the second line of text, and through the letters "rty" in the word "Liberty" in the first line. The crack ends near the attachment with the yoke.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed