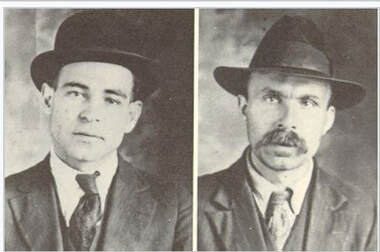

Daniel and Abigail Shays' Pelham, MA farmhouse, c. 1898

Daniel and Abigail Shays' Pelham, MA farmhouse, c. 1898 In 1787, Shays' rebels marched on the federal Springfield Armory in an unsuccessful attempt to seize its weaponry and overthrow the government. The confederal government found itself unable to finance troops to put down the rebellion, and it was consequently put down by the Massachusetts State militia and a privately funded local militia. The widely held view was that the Articles of Confederation needed to be reformed as the country's governing document, and the events of the rebellion served as a catalyst for the Constitutional Convention and the creation of the new government. There is still debate among scholars concerning the rebellion's influence on the Constitution and its ratification.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed